Fran Hayes

About this interview

Fran Hayes reflects on her history of activism in the Australian Social Welfare Union (ASWU), campaigning for the CYSS award and achieving a win in the face of opposition from employers and Government that forever changed industrial relations in Australia.

Transcript: Fran Hayes Interview

START OF TRANSCRIPT

Facilitator: So, I'm just going to ask a very broad question first, Fran. When did you first get involved in unions?

Interviewee: I graduated from university in 1976 and I first got involved in 1977. And it all happened very rapidly. I was involved in my final year at university with a group called Inside Welfare. Social work students. And they campaign mainly around rights of welfare recipients. There was a branch of them in Sydney and there was a national meeting that I went to at one stage too. So, this is at the end of my university. Possibly early into the first year out. No, I think it was uni. So, my first job after graduation was actually in Albury-Wodonga. And it was a project about home-based services for people with disabilities and the elderly.

Then I came back to Sydney mid '77 and started looking for a job. And it was a particularly bad time then for social work graduates getting jobs. So, I thought I'll do some volunteer work. There must be something I can do to keep my head working. And I went down to a place down here it used to be, called the Inner [Sydney] Regional Council for Social Development. That was part of a major Federal Government program for decentralisation. So, there was the Albury-Wodonga Development Corporation was the government body and the social planner in that organisation requested me to do this study on home-based services.

Anyway, I came back and went into the Inner Sydney Council for Regional and Social Development, looking for someone to talk to about some voluntary work. And I met a guy called Bob Boughton. I had never seen him before. I didn’t know anything about him. But he got talking to me and he was connected - I got the impression definitely that he was connected with Inside Welfare too. So, there was a bit of a common ground there of us coming together. Anyway, as I say in the book…by the end of my chat with him, he had signed me up as a member of the ASWU. Very new union at that stage, it was formed in a technical sense in mid-1976. So, this is mid '77. Bob signed me up to the union. He told me I would be in the inner-city branch. The inner-city branch was meeting that night in the very building we were in. I went to that. At that meeting, we were informed that the Trade Union Training Authority, for which I later worked, was running a special course for us that week on how to get a federal aboard. And it would be really good if we had a good showing there.

So, he asked me if I'd go to that, and I said yes, I went to that - I went to a three day course on industrial relations as applied in our situation. And then I had been told that there was a national award campaign. That the union had recently adopted a resolution to gain a national award for our members in the community sector. A federal award covering all states. I got a little bit involved in that and before I knew it, I was the New South Wales NAC committee delegate. So probably a week after I joined the union, I was flying to Melbourne as the New South Wales delegate to the National Award committee.

Facilitator: So, did you say a week after you got involved?

Interviewee: Mmm.

Facilitator: Right.

Interviewee: There was a very unique way of organising and it was quite amazing when I look back on it. But yes, join, do training - join, attend a meeting, do the training and find out a little bit about the National Award and become the National Award campaign delegate for New South Wales. We had a meeting in Melbourne where we discussed the award. We then formed a tight little group called the NAC executive. That was the National Award Campaign executive. That consisted of Bob, who, by this time, I'd found out Bob was the Federal President of the union. He was doing a PhD. None of these jobs were paid jobs.

So, he got me, one social work student who was on placement there at the union, [Kim Anson], another social worker like me, new graduate having difficulty finding work, [Ann Wright]. So, there was Bob, Kim, Ann, myself and later, a guy called [Steve Mills]. He was on that committee for many years. But he went to live on the North Coast to have a change of lifestyle and so on. So, the NAC [executive] was basically five people and we then had to sit down and work out how we were going to get this award. So, my introduction to unionism was, I probably didn’t set out to join a union and get active, even though I was pro union.

And suddenly all this was happening. All of it was unpaid of course. But it was really interesting. Then we carried on for a few months getting ourselves equipped to seek this award. We got professional advice from the union's lawyers. But also, we got advice - Bob was allowed by the federal executive to - what's the word? Not enlist. Employ as an advisor to us, a guy called Jack Hutson who was famous in the left of the union movement in Melbourne in the earlier days. And he wrote two remarkable books. One is called Six Wage Concepts and the other one was called From Penal Colony to Penal Powers.

Bob knew him and the federal executive said yes, we could retain him a as consultant. He gave us a lot of very good information on both the logistics and the politics of getting a federal award. So that was it. We had our legal advice, we had Jack Hutson. We had - no one on the federal executive was really interested or involved in the award campaign. But they did keep approving things we did up to a point. So here we are, the five of us, having had that information, that training from Jack. TUTA to some extent. Our legal advisor in Melbourne, our lawyer, Simon Williams, who worked for - god, what's the one that Josh Bornstein works for now? Maurice Blackburn.

Facilitator: Maurice Blackburn.

Interviewee: Yeah. Simon Williams worked for Maurice Blackburn and he married Josh's mother. And Josh seems to be the face of Maurice Blackburn these days, which is very interesting to me historically. So, it was agreed that we had to employ someone to get the award going. And t he Federal Council approved that. That someone be employed for three months to achieve the award. And all things being equal, that person should be a woman. So, we called for applications. Then we, the NAC executive, interviewed - read the applications and interviewed two people. We weren't happy with either of them.

Next thing I knew, Kim and Ann went out to the kitchen to make coffee, spent quite a while out there, and then came in and said we want you to do it. We haven’t had any suitable applicants. You do it. I thought oh god. Because by this time, I had got a job. But they…

Facilitator: In social work? Or…

Interviewee: Yeah, it was actually in the [CYSS] scheme, community youth support scheme. I was a project officer at Fairfield. And they knew what I'd been through to get a job as a new graduate but they said take leave, take leave. It's only three months, take leave. So, I persuaded my management committee to give me leave. They never saw my face again of course because three months was ridiculous.

Facilitator: I was just about to ask you, I've written down three months. Because three months to achieve an award from nothing in an industry that wasn't yet an industry.

Interviewee: Look, it's one thing for people to write a list of what you have to do to get an award. Then says oh well, that looks good. It's another thing to do it. And we had no idea how long that would take and they did keep renewing my appointment. The federal executive kept extending me. We, we set a - yeah, this was how the first problem came up. To go for an award as the ASWU, we had to change our eligibility rule because it was the old professional social workers' one about university degree and blah, blah, blah recognised by the ASW. We didn’t want that. We were there for the community sector. We weren't favouring professionals over anyone else. So, we had to change our eligibility rule.

That was a massive job which took about three years to complete. In the end, we had to log for our - serve our award, a lot of the claims, still using the old rule and just trying to talk our way out of that in the commission when they asked us how come this said this when we were doing that? There were a number of friendly unions who objected to protect their own area's coverage and settled very quietly and pleasantly. But there was one union that was a right-wing union with a very strange guy representing them. They literally tied us in knots. They didn’t just want a letter of undertaking that we would not be active in their area.

They wanted it written into their rules and very - yes, that's the real hardball end of rule changes. When they want it in your rules that you will not take their people. And that went on for so long. Anyway…

Facilitator: So that was one of the things that made the rule thing drag out?

Interviewee: Yes, yes. Definitely. Definitely.

Facilitator: I'm not at all asking for names or to implicate, but that union had members in your area? Or had thought they could have members in your area? What was the area of demarcation for them?

Interviewee: There were two. One was public sector. State public sector. And we didn't really want their people anyway. Most of them just went away quietly. The local government similarly. But this one wanted to protect the state public sector and also the registered charities that covered - one group in Australia that had an award was social workers working in registered charities. We're not talking about the New South Wales PSA but if you like, this group oversaw them. Very different people now. So, in the course of all these negotiations and our lawyers would come in with us, I mean we didn’t know. We thought rule change, it can't be that hard.

And then when all these unions objected, we thought oh my god, are they going to wipe us out? Is this going to be the end? And of course, we had to learn the hard way that this was standard practice for most of them. But we didn’t know who that covered. We didn’t know who they were. In those days, they didn’t have the IT that they have now in the registry. And we had to get the books, the big yellowing books handed to us at the counter to read their eligibility rule and their coverage. So, one thing that slowed it down was our total lack of knowledge of it. But the other one was a very deliberate attempt to tie us in knots, to stop us getting it changed that could in any way affect their people.

I think we got it in the end. It was after my time. But they did make a mess of the eligibility rule. Anyway, that, that problem has gone of course now with the subsuming of the ASWU and of the ASU. But while we were doing all this stuff and having lawyers in, they started to say look, some of these people are making threatening noises. I think that was the first place it was actually raised with us, was by that organisation. That you can't get an award anyway because you're not engaged with people employed in an industry. So, the lawyers said well, yeah, okay. This is going to be raised. This is going to be a big issue if it's raised.

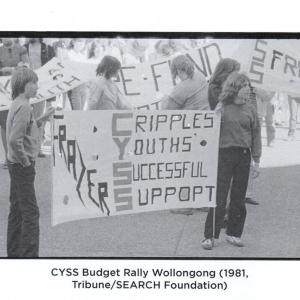

Because the standing, the position of the law at that time was you couldn’t have a federal award if you weren’t engaged in an industry. Not in employment. In an industry. As you probably know very well. So, then we had all this soul searching and we decided okay, and our lawyer, our barrister - we had one solicitor, one barrister. The barrister said look, if you want to serve a lot of claims, you're going to have to do it in an area that looks like it's industrial. So, we chose the CYSS program. The CYSS program which started in the mid-70s, which was the Federal Government under the Fraser Government. When did I got to CYSS? I went to CYSS in 1977 and it had been around for a couple of years then. It was definitely under the Liberal Government anyway.

And it was designed for unemployed young people. And depending on how creative the people were who employed them and their management committees, it could be somewhere where they'd really learn some useful skills. Or it could be a drop-in centre where they just hung around all day and so on. The one at Fairfield that I worked in briefly was pretty typical I think, very disadvantaged kids. Some kids from Fairfield had never been to the city. We had a beach outing one day and one of the girls said this is the first time I've been to the beach in my life. It was yeah - I mean you couldn’t promise them jobs. Firstly, because there weren't enough jobs but also some of them would never be employable.

Just where do you begin? Although I did get a very disadvantaged young guy a job and he did really well. He was almost infantile in his behaviour and appearance. But he got a job and I think he kept it for quite a while. Like his view of the world at that stage was that he wanted to get a job in Woolworths behind the counter. And I think even by then there weren't counters in Woolworths. So, the CYSS scheme was considered to be the closest thing to industry because you're helping people get a job and people in some projects were doing things like - what do they call it? Screen printing, that kind of thing. Craft-related things.

And the other thing was in CYSS, in Sydney, but also in other states, we had very strong membership. We had members in CYSS were really good value. So, we had a number of people in the Communist Party in our CYSS project and they provided unbelievable support to the campaign. So, here we go, 19… mid-1977 or late 1977, I was appointed to get the national award in three months. So, we're now up to the first hearing, is in July 1979. And I won't go through all the details because you've got the book and it does it in pretty chronological order. But we had to fight… awards industrial relations was all new to CYSS employers and CYSS employees, management committee.

Management committee, some of them were absolutely terrified what it might mean for them if they agreed to an award. It was certainly not - and similarly, members were worried they would lose their jobs if they supported the award. In some cases, that would have been a realistic fear. We were handling some dreadful unfair dismissals in CYSS for the most ridiculous and petty things.

Facilitator: Can I ask, just for a bit of clarity around CYSS. So, you're saying there's local management committees? Okay, so it's funded by the Federal Government?

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: The local management committees are comprised of?

Interviewee: They may be local government people. They may be people who work in the social welfare industry and as part of their job, do some time on the CYSS committee. So, people from FACS, people from local government. People from all types of community organisations around that area was generally what they were - sometimes there were church groups. I think that was about the look of it. And they didn’t - apart from the ones who were just blindly anti-union, a lot of them were just scared. They didn’t understand it and they didn’t know what would happen to them if they agreed to it. And, of course, the government capitalised on that incredibly.

So, we've got management committees who, it was actually a technical point, are they the employer? That was settled. We got through that bit. Yes, they are the employer in this instance even though they don’t control the money. And that definition of the employer in the community sector remains today. It was settled there and then and we have a nice little letter of advice from our barrister telling us why he thought they were the employer.

Facilitator: Isn't it interesting, that concept of who is the employer is still such a live issue today in so many areas.

Interviewee: In this case though, I think the employer concerns were different. They didn't know what an award would mean. They didn’t know what would happen to their project. They didn’t know if they were going to be held individually liable if they lost funding and couldn’t pay them. So, there were some fears that they were unique to an area that's never been unionised or organised. And it became pretty much par for the course through this campaign that we were organising the employers as well as the members. So of course, what the government did next, they called a meeting in Sydney of all the CYSS schemes in New South Wales.

Kim and I went and we were actually allowed to listen for some of it. But we were kicked out if they were doing anything strategic or voting. And we actually got a chance for us to say what we thought we were doing and why they didn't have to worry. But the government just told people that they may be found legally liable to pay the salaries if the funding was lost or the funding was inadequate to cover the award, and they had a barrister just on standby to advise them more on that, and they had discussion on that. And what they wanted was for the employers to oppose the finding of a dispute, and hence the making of an award.

So, this meeting was all geared to that. A lot of money was spent to bring these people together. Kim and I were in and out. John Sackar was the barrister. I think he's a judge now. Government blatantly paid a barrister to represent people if they would vote against the finding of industrial dispute. This is what we were up against. And when they left, with a decision to oppose the award, there was a Telecom strike on, a good old fashioned Telecom strike was on in Australia. In those days - you're probably too young to remember - but if Telstra went on strike, what would happen - if the technicians went on strike, what would happen was every time something dropped out, it was left.

So the system gradually grinds to a halt. Of course, the Department of Employment and Youth Affairs - this was our enemy - they sent 115 telegrams to the committees about what they had to do or not. We didn’t have any hope of sending out telegrams like that. So, they were ahead of us in that sense. But we got - I mean we still laugh about it a lot - somehow, we got the message out all over Australia with our contacts, without telephone. Like people who would go, getting on train - a plane to Perth or people getting on a plane to Adelaide, we gave them all material. We used to say that we used carrier pigeon. But one way or another, the word got around.

And on the day of the first hearing, which was an incredible day for us, when people were giving their appearances and so on, we had been able, by our sheer hard work since the employers meeting, to get a group of employers who said they would not oppose an award and they would not oppose a finding of a dispute. At that stage, the other side had more and they were well resourced and they had a barrister provided. None of this fronting up and just making the appearance yourself, they had the whole works. And the Commonwealth Government had a barrister too. So, the bad guys said theirs first, I think. They had, I think, 27. It's actually in the book.

I think they had 27 committees opposing the award. Then we had - none of these people had any experience in the [commissioner]. We had a guy called – oh, what was his name? John? Anyway, he stood up for, I think, 13 committees and said they did not oppose to making of the award. They did not oppose the finding of a dispute or the making of an award. They're consenting to it. And so here we had an impasse. The commissioner, who was Deputy President, Joe Isaac, he had some employers here saying don’t find a dispute, some here saying do find a dispute. And we're ready. We're ready to negotiate and finalise an award.

Our barrister stood up, Jim Kennan, lovely, lovely guy. He died a couple of years ago from melanoma. He was the loveliest man. He was from Melbourne and he was closely connected to Simon Williams, our barrister. He got up and said, how about the option - this is not the words - how about the option of making a provisional finding of the dispute? He said the commission has within its power, to find an industrial dispute and to allow any parties afterwards to seek revocation of that finding. And the commissioner went for it. And so, we finished up. We had an industrial dispute and a very angry government.

Facilitator: I can imagine.

Interviewee: Someone, I can't remember who, there were a few wise heads in the union, some had worked for other unions. They said you ought to go and see Joe Isaac. You ought to just go and see him and tell him what's going on behind the scenes. He'd probably be really interested. I thought gee, I never heard of going - you know, when you [unclear], you've served a lot of claims. But anyway, Joe, he only died a few weeks ago. He was 97. So, I made an appointment and then I went in and told him exactly what had happened with their organisation with the employers. He was very professional.

He didn't take sides or anything. But he was on our side. He thought it was outrageous what the government was doing. He made that very clear when I bumped into him somewhere a few years later. So, our thing then was to go away and negotiate an award with the committees who were prepared to do that. And we did negotiate a pretty good version of an award with those people. But then when it was called back on, the government really came in strongly again and opposed the finding of a dispute with revocation. They just wanted it found and they wanted to get on with it. Isaac found there was no need to revoke the dispute and they said righto, well we're appealing against that.

And that went up then to the full bench and so on. So meanwhile - we were negotiating the award with the employers who were friendly to us, but meanwhile, things were getting meaner and meaner. Like more and more it was being said that we didn’t have a hope of getting an award anyway on a jurisdictional sense so they would be arguing that. It was a full bench - I'm getting mixed up. There was a full bench hearing about the revocation of dispute and Isaac lost. He had one commissioner in favour and two against. So that meant okay, no award. We're going to be hit with the industry definition wherever we go.

There's only one thing we can do if we want to keep going and that's to go to the High Court. And Jim Kennan said he'd do it for free. And we then had the most horrific fight within the union about this. Running alongside all of this happening with the CYSS case, we had - the Victorian branch of the ASW was the largest branch. They had the most members. They had a new very determined organiser. A very politically savvy ex student activist type very smart organiser. And she had made of course a good study of how the union allocated its budget. And up ‘til that point, the union had allocated - had given one third back to the branches and kept two thirds.

And that was just enough to run the federal office and pay an organiser. So next Federal Council, the Victorian branch just came out all guns blazing. Lobby, threatened, seceding, the whole works, and they won. They of course threw in quite a bit about how the CYSS award was useless anyway and we were never going to get it and it was throwing good money after bad. And they got it and they got their organiser then in Victoria to be a fulltime organiser and no money to employ me. And they knew that and that's why they attacked the award claim itself. And then I remained in various honorary positions probably for another four years.

I had a term as Federal President. I had a term as Vice President. But I couldn’t work there. And I was sort of in my late 20s and had to start thinking about things like saving to buy a house some time. I had to get another job. I couldn’t just go and be a union activist for nothing. So I got a job with the Trade Union Training Authority. I was the first woman trainer appointed at the Clyde Cameron College. I'm very proud of that. I'm still very proud of that. The stuff with the award bubbled along and the time came to appeal to the High Court. And Jim Kennan had meanwhile got elected to parliament and been made the Attorney-General of Victoria.

So, he couldn’t do that. He couldn’t even let on he knew anything about it because it was federal and he was a state politician. So, he got a guy called Peter [Grey] to do it. Meanwhile, I was sort of huddling a bit on committees and things in the ASW but I was in Albury-Wodonga so you know. Anyway, it was heard in March 1983 and the New South Wales branch people were looking after it and one of them, Carol Matthews, who became the National Secretary of the ITA, she rang me. It was heard in March, just after Hawke was elected. She rang me in July. She said the finding is in. The hearing is done. I said how did we go?

She said we won. I said how many by? She said it was unanimous. Now, that had just a really good unifying factor with me about it wasn't all for nothing.

Facilitator: Yeah, absolutely.

Interviewee: There was a nice conclusion to that part of the union's history. Of course, there were a lot of things - a lot of things come together for that kind of shift to happen. Change of government. Federal Government gearing up to support the freeing up of the definition of industrial dispute rather than keep it clamped down. So, we had the Solicitor-General idea. So, in effect, we went from having the Federal Government fully against us in every forum, to having them supporting a broadening of the definition in the constitution. Because it had - I mean I'm not just saying this because of our situation. They had really got it down to such a narrow definition.

But a lot of unions still had not been able to get into the federal system at that time because of that. They more or less said look, we've stuffed this up. We've tied ourselves in knots. This has been going on since we first started operating and it's been made too technical and the common-sense interpretation of industrial dispute should be a dispute between employer and employee about working conditions. That's an industrial dispute. So, they really swept it all away and there were unions who were absolutely ecstatic because they were able to go in for the first time.

So yeah, we did that and then I was no longer working for the union, but people who were, who gave me the information for this part of the book, overlooked the making of the actual award. It was Minister Ralph Willis in the Federal Government, apparently made it his mission to get this award finished, up and running, and have the employers and the workers educated enough to handle it and supported enough to go through the technicalities of getting the award. Right. So the award - High Court decision was in 1983. The award was finalised in 1985. So, we served a lot of the claims in '79.

So of course our Victorian branch had a field day writing all the time about how we were wasting money and it's a pathetic thing and the union is a laughing stock, this sort of thing. I was reliably informed afterwards that when the High Court decision came down, they all ran around taking credit for it. But I kept a copy of what one of them said about it and I actually put it in the book. Just thought I'm going to, I’m going to give myself just one little opportunity here to say…

Facilitator: To correct the historical record I think they call it, Fran.

Interviewee: It was really good. He definitely had a way with words. Look, I won't get - mirage. That's it. We were throwing money away on an industrial mirage. [See image 1 below]

Facilitator: Oh. Nice. It wasn’t so much a mirage in the end though. Well, look, I'll go back and source some things from the book if that's okay? Cross reference to it as well and maybe some of the images if that's all right? If you'll allow us.

Interviewee: Yeah, sure.

Facilitator: Thank you for that because I mean historically in Australia, that's an incredibly important story in the development of the industry and your award. But I'm also interested in you and why you did what you did and what you did next as well. So, you mentioned to begin with that previously, before you went to that fateful - to the office on that fateful day, that you weren't involved with the union but you were pro union. Did you have a family background that led you to that?

Interviewee: So just the first point is that the union itself in my industry as a community worker was the ASW and it was still a very new union and all of that. There was no other union. So, people were being asked to join something that had no award and so on. But my parents were certainly Labor voters all their lives. And I just picked stuff up in various ways. Like one night I remember when I was probably at uni, there was a strike being covered on TV on the news and various comments being made. And m y father just said the people who don't strike are not fair because they don’t lose any money but they get the benefit of the final industrial action.

So, you should always be in the union and participate in the way the union makes decisions about these things. So, there wasn't anyone in the family who was a union official or anything like that, but there was a very solid family history of just that basic, I suppose, Labor view. That unions aren't evil. Unions are here to make things better for us. People shouldn’t bludge off other people who join and pay, and you should be in the union wherever you work. That was the extent of it. So, I mean even though it was not contentious in any way, it was pretty important, I think, the messages that I was getting. And I was never told anything like don't join a union or unions are ruining the country.

Or never anything like that. I had an aunty, aunty and uncle who were very, very strong Labor people and their oldest son was a Labor activist. And he was actually a union official in Sydney in one of the bank unions when they all had their own union. And he was in that around that time too. So, George was a union official. He was a secretary. Again, it would only be mentioned in passing, but you'd never hear things like what's he doing working for a union? My family were not anti-union. I never heard any criticism of unions taking industrial action or anything like that.

Facilitator: So, once you had to get a paying job - actually, before that. So, there was a period when you mentioned the situation with the Victorian branch and then your paid position stopped but you continued your activism for some time. So, in terms of how you managed your activism, your real life, having a job or finding a job, could you talk a little bit about that?

Interviewee: Even though I was very disappointed by the decision, it was by one vote. I still had a lot of supporters. So, I was prepared to - I actually agreed to work part time over a longer period. Let's say there was six months money left - or three months. I said I'd do six just to keep things moving. And then it was established that we'd actually have a proper national industrial committee which was well overdue and which drew the states in better. I was actually the convener or chair of that committee. So that went on for some time. It was very, very damaging to me though, what happened. You know. It was a very difficult time in my life, getting over that and moving on.

Because - I mean we were all - I was the one who lost my paid job but we were all equally distressed about what had happened. And the one thing I've always said is that whatever I did and whatever the NAC executive did, we reported on and got approval every month from the federal executive. And in the end, it was the federal executive that turned on us. And they lobbied very heavily of course that Victoria would secede. But we weren't doing anything underhand. We had always reported and there had never been any question about any of it. We, we felt that we'd been approved.

Although, I'd have to say, some of the tensions between the idea of the union and the old idea of the professional association for social workers was that maybe for people who had been in the professional association, who were on the federal executive, including the federal secretary, I think they were getting quite frightened about what could happen. And I think they thought maybe we should stop trying to get the award because look at all the money, look at all the - and they seemed to think they had an option not to get an award. It was like this has all been expensive, drawn out and inconclusive to date.

Why don’t we just get back to what they used to call social action?

[Aside discussion]

Facilitator: So you were just telling me about I guess the personal toll of that very intense period.

Interviewee: Yeah, it was a very heavy toll. The other people who were working with me on the campaign, they at least had their own jobs and all of that. So anyway, I didn't doubt, I didn’t doubt that I would have to find another job soon. I did a whole lot of bits and pieces of part-time work over this period. That was okay. I did a little bit of work at Sydney University at the social work department. And I was looking for jobs and I saw the training officer for the Trade Union Training Authority in Wodonga. My friend, Ann Wright, who was living with me at that time, she said look, this could be right for you. And she said, I know someone who has worked there and I can get them to come here and tell us about it.

So, it was this guy, John [Tui], who is an academic at Swinburne now. He had gone there for a bit of a stunt down there to the college as a trainer. She got him to come around for dinner and he told us all the things about the working conditions you had and the hours you worked and so on and so forth. Told me how I could best win over the national director in an interview, which I didn’t take that advice which was to emphasise my Catholic girls' school education, no, I'm not going to do that. Sorry. I'm not putting it in the application. But anyway, he had mostly very interesting information on what was available down there.

Meanwhile, Sydney University offered me a job as a tutor and it was all deftly secret because I didn’t accept it and I didn’t want the person who got it to think they'd missed out. That person is now deceased I understand. But no, I looked very hard at Albury-Wodonga and the uni and at the resources because there at the uni, and it's probably worse now, it was a big deal if you had to make an STD phone call. It was a big deal if you did any photocopying. Here we had this purpose-built training and college down here with everything laid on and paying better than the lecturer. So, of course, there was the issue of having a long-distance relationship and that sort of thing was definitely an issue.

But I thought it would be good. And I thought it would give me - if I could do a few years there on that pay, I could save up towards a deposit. So, I went down there. The national director at that time was based in Sydney, Ted Heagney. And he knew I was concerned about things like being away from Sydney for a long time, how often I could afford to come up et cetera, et cetera. He took me out for lunch at the Mandarin Club to talk me into taking the job. And he said look, you weren't just an organiser, you started a union. And I didn’t really but you know, we were there in the building blocks of it. So, he was really keen.

At some stage, a waitress came over to him and said there's a man over there who wants to buy you a drink. Ted looked up and he looked over and he looked both angry and embarrassed. I'm completely oblivious to this at the time but found out later that Ted mentioned in the office that he was taking me to lunch and this guy, who is the righthand man, came to look at me. As someone said who knew, to have a look. Ted was so embarrassed because it was made pretty clear what was going on. I thought oh god, this isn't a good start. But I went down there and I absolutely loved it.

Apart from being the most physically well-resourced workplace I ever had and will ever have, it was public service conditions and merit selection at that time. They still followed that. And there was even a special agreement for the college trainers made by the ACLA as it then was, to take into account our hours of work and so on. Also, unlike the union, we were not expected to set foot in a training room until we'd done the three-week residential trainer course, union trainer's course. And also, we were never left alone in a room to handle a difficult situation. There was always another trainer.

So, it was the exact opposite of the union. I thought this will do me good, even though there were long hours when we had courses in, overall it was much less stressful. Plenty of quiet times and times just chatting with the people you work with and so on. We all had our own individual office looking out. I mean you either love it or you don’t. I loved the environment down there, the physical environment. You're looking out at jacaranda trees and so on. You're meeting incredible people coming on the courses. Women were in a minority of course. Back then, always. But I think we made it work pretty well, I think, overall.

It was me and five other trainers with varying degrees of experience there. A guy who was sort of between unions with us, nursing his wounds from a union stoush and moving through to another union. But he had a year there with us. He was a lawyer and he was brilliant. Wrote brilliant training materials. Case studies. Very bright and very amusing and funny.

Facilitator: So were you the only woman?

Interviewee: I was the only woman at that point. The only woman who had ever been appointed to the college. There would occasionally be a bit of a secondment or something. Not even that. A bit of a helping on a course. And it was going into a public service environment, you know? Superannuation, salary increments, rights of appeal, special agreements because of hours of work. I mean it was - there were some things about it that were very different from what I expected. I learnt that people who join unions or even leave unions, do not necessarily have progressive attitudes on anything else.

And that was, that was an eye opener for me because in my industry, it was a new union, you had to be pretty keen to join anyway. And when you joined, it was for your political reasons. And I wouldn't have imagined some of these people, how they could have joined let alone led a union. But the, you know, racism, sexism. One of them, they did a mock up of a demonstration saying something rights for gay whales. I mean there was quite a lot of that around. And I'm thinking this isn’t my idea of a union mentality - union position at all. But I had to realise that unlike my case, where even though it was done pretty swiftly, I chose to join. I identified the organisation with progressive ideas and practices and all of that fitted together. But you would get people with racist or sexist or anti - well, they're not anti-union, they're pro union. With these negative attitudes that seemed inconsistent to me with unionism. They had joined the union for who knows what reason. They had sought leadership possibly just to gain influence. I mean unfortunately, a lot of people who have succeeded in union leadership roles often didn’t have formal qualifications of any kind. This was one area where they could get work and if, depending on the union, well-paid work, without having values that matched it.

And, we all know about the SCA, like an organisation that exists to populate the right-wing places at an ALP national conference. Those people don't have progressive views. They don’t even really have union commitment in the sense of doing anything useful for their members. And so that was a bit of a challenge to me. But I never had arguments with participants about it, it was fine. The participants behaved really well with me. I was asked in the interview if it was a code, it was a code question for something. I was very young, a lot of the people who go to the college are quite old. How do I think I'll manage?

What it really was, was I'm a woman and a lot of them are men and how do you think they'll manage? But I just answered his question as he had put it and said of course I worked with a lot of older people in my original union. I figure my secretary was well in her 60s and so on.

To my knowledge, I never had any trouble being accepted in my training role by people in a course. I did see situations where one organiser's course I ran with a visiting trainer. There were a lot of guys who were Telstra linesmen who came to that course. It was very male dominated. And when they saw not one but two women greeting them to the course and no men, it was really obvious to some of them that that was really confronting.

They probably wanted their money back, you know? They just weren't prepared at all for two women. But that course settled down well too. A lot of people from non-metropolitan areas are in the union movement. In fact, they're more so now. The sense of humour, the larrikin sense of humour, I just loved it. And it was always there. Always there. Even with women. Some of the funniest things they'd say. And it was like - I know it's a bit out of date but it was like the old Australia still, that there was something there about that unique approach to life. That, I mean I still see it when we go to remote Australia. We don’t see it in the city at all. And a lot of it is very positive but the humour is – oh, some of the jokes and stories I heard.

But also, the humour just on the spot was really fantastic. It was really good fun doing this work. I found because - this was very early in TUTA’s history and especially the college's history. They had begun, right from the beginning, with a progressive teaching methodology. Learner-centred learning. Learning to think critically. And learning how to prevent and resolve conflicts as they arise. So, we had a whole technique which didn’t happen anywhere else in TUTA I don’t think. In a residential course we would start with saying that they would schedule half an hour each morning before the session started, we called it clearing house, and they were to use that to identify and resolve any issues.

So, it might end up with my bulb isn’t working in my bathroom in room 10. And we'd get that on a slip of paper and pass it on. But arguments that had happened the night before in the bar, tensions, sexual harassment in some cases. They would attend and use that time to resolve those issues. It was a very, very important part of the way we worked. And overall, the courses were not difficult to manage if you employed those techniques. I was amazed how well people really did behave. Certainly, in the training room. I certainly didn’t get made to feel that I had no credibility and they didn't have to take notice of me. Sometimes I think they'd get a bit of a shock. They'd realise I knew what I was doing and they weren't going to challenge it.

Facilitator: A couple of questions around this but even before that. So, you got thrown in, colloquially we’d say, the deep end when you started with the union. And your role was a leadership role in a sense, driving the campaign. What made you so ready to accept that so quickly and what characteristics do you think you have that meant you were a leader in that space?

Interviewee: When you say why I accepted it so ready, why I accepted what?

Facilitator: Yeah. The leadership, you became - you went on to the national committee really quickly for the award and then you were their person effectively running the award campaign. So, what is it about you that you were able to step into that?

Interviewee: Well, I have to say, and I'm always saying this to the ASU because they praise me and give me life membership and it really was a collective effort. It really was. The ones who weren't paid considered themselves equally responsible. We did it together. We did every significant decision together. Like the day that the department brought all the employers in from all over the state, Kim was beside – the two of us are doing it equally, equally deciding strategy, not on my own. I was also working in that process with two remarkable leaders. Kim has gone onto very senior roles and is the CEO of a major consulting firm at the moment.

She was an amazing leader. Bob Boughton was an amazing leader. I didn’t really see myself as a leader. I didn’t think oh I'm stupid and I don’t know anything. But I think I'd be not doing justice to the others to say I led. Okay, federal president, I got the job of chairing the national industrial committee after I'd finished working there. The others who managed to get on the committee to work with me were those very same people that I'd worked with. So I never, I never saw it as well, it's me against the world. It's certainly the NAC executive against the rest of the union, or some of the union. But I did not feel that I should have credit for the leadership.

What I did and how I did it was related to wanting to work hard for - being prepared to work hard for something important. And being prepared to stick at it, that's probably one of my major qualities in the things that I've done, is that I'm a stayer. I think I probably didn’t recognise it back then, but I think also my interpersonal skills were very good and that made a lot of things easier for me. But I didn’t think I, I got this award, I set up this committee, I did all of this. Because we really did work very closely. And a s I said, I was with other leaders. I think probably now, I'd be much more - if I wanted to work again, I'd be much more conscious of those qualities and I'd probably develop them more too.

But it was - what did we say? I saw Bob at something last week. We didn’t know what we were doing. We knew… but we knew we had to get an award and we told the members we'd get an award and I would not turn my back on someone that I had promised something to which was a valid thing to be wanting anyway. We could have ended up with nothing and I would have said well, that's five years of my life really wasted. It wouldn’t have been really wasted but it was a whole lot nicer actually getting the decision and that pulled everything together and wow, this all has made sense. It all fits a pattern and we've won. We've got a lot to show for it.

So probably after that, I was more confident in some things. But also, certain negative things happened too that were a bit of a dent to my confidence. So, alongside the consistent working day to day and feeling I was able to manage and control the course, I had a lot of trouble with management. I was always in trouble. And sometimes they did things to me which were really hurtful and which really were damaging to me. So, it was very strange. It was okay, we've appointed a woman but she's going to be docile. You know? Aren't you happy we've appointed a woman? And I went in there already with a view about sexual harassment.

Because even though I believe sexual harassment is greatly over estimated, I think a lot of things went on at the college which I would call consensual sex. Not sexual harassment. But there was sexual harassment. So, when I went there, I just automatically - and I suppose this is leadership - I automatically just - I had been sexually harassed as a participant on a course a couple of years before. It was actually a union, it wasn't TUTA, it was a union conference. The guy who did it to me was from that union. They had their own little investigation pow wow, which I was of course never involved in and found out about years later and their way of resolving it.

It made me absolutely powerless, the way they resolved it. So, I said righto, now I'm at the college, I'm going to make sure that doesn’t happen. I'm going to get some procedures for that. We've got to get women's courses and we've got to get childcare. And I just - I don’t know why but I just thought I had to do that. I had to do that, I had to take responsibility for it. And I get it and it led to a lot of clashes. But we got a very good policy and procedure for sexual harassment where I don’t think anyone was really stuffed around as much as I was when it happened to me. We got women's courses. I'm writing a little bit now.

There's a TUTA history being developed. The women's courses was a very mixed bag. You could say in some cases, women's courses were set up to fail by the actions of male officials in who they sent to the course. Sending people to a two-week residential course who did not have the capacity mentally to cope with that material and who got disruptive for that reason. Sending women to the women's course only because it was a women's course so they wouldn’t be near men who could bother them. So, send them to a women's course. But needless to say, there were women on the courses at the college who were not feminists in any way, shape or form.

So, I had various demands about women's courses. In the course of the TUTAs existence, I would call it error to elation for women's courses, because a lot of things went wrong early on. Especially the residential ones. Especially when they were run by all men. And the…

Facilitator: So they were run by men?

Interviewee: Run by all men. No women trainers. So, we'll run a women's course. And they were not equipped to run a women's course. Legendary some of the things that went on [in] that course with trainers. So there had to be some standards about women's courses. There were these issues in the early courses. There was a terrible one where I was away on leave working somewhere else and again, all men, all men around a women's course. It ended up a complete mess. It was. People were being threatened with being charged with criminal offences, written complaints being made by a lawyer who was on the course.

But you know, you get - I know we don’t use this term anymore, but in those days, you get a group of separatist feminist women in a two-week residential course run by three men, you're going to get trouble. And, oh It was just dreadful. When we moved on to the national women's forums, probably late '80s and the ACTU women's committee would determine the topic in consultation. So, it might be part time work. It might be women in non-traditional jobs. Various topics of interest. And they weren't coming to learn skills or learn how to be a union official. They were coming together as women in this diverse industry, or in one industry if it was the case of say part-time work in the finance industry.

And people would be talking about what happened in their industries and what strategies they used. And we had guest speakers who talked about all of that. Now, one of these forums, which we called it the women in non-traditional jobs and industries forum, WIMDOI, we ran that in 1995 and it's still running. It's huge. Still running. So certainly, the format of forums has been very successful for women. But some of the earlier stuff was a bit ham-fisted. And so, I had my views about women's courses. One of the guys who was responsible for adult education teaching, one of the trainers, he had the idea of getting it. We got together a women in union training seminar in 1983.

And that brought women trainers from unions all over Australia and it was a strategy-setting [forum]. It wasn't an information setting [forum]. And some of them were very, very experienced and good thinkers. And so, we talked about things like women in male-dominated courses. So, we're still going to have women in courses and they need to be in mixed courses. What can we do to make things better for them? Women in women-only courses. What's the rationale for women only course? Is it to help people build their confidence? Or is it to allow experienced women to strategise together? And just unpack all this stuff about women's courses.

And one of the women, who was a pretty full-on activist in South Australia, she said righto, all that stuff we've just done on butcher's paper, we've got to send that now to the head of TUTA and the head of the ACTU and the Labor Councils. And it all got packed off and sent. Of course the poor things, they couldn’t understand a word of it. And so, Ted Heagney said to me, I've had an angry response from two Labor Councils. Ted came to the college from Sydney and all of us who had worked on that course were taken in individually. I felt that day that if there was any way legally he could sack me, he would. He was furious. Absolutely furious. They asked for our childcare policy. I asked for the file on it and distributed it.

They asked for things to be sent to them after the course by overnight express. We were banned - the staff were told that they couldn’t send overnight express for us anymore without showing the contents to our director. Staff were not permitted to give me a file ever again without asking permission from…

Facilitator: To give you a file?

Interviewee: Give me a file. Because I went and asked for the file on the childcare policy. And they’d had, they had a policy. I'd put a proposal in and they'd rejected it. They were furious that I did that. So, no more files to me. No more parcels. And to any of us who were involved with that. Were not allowed to speak on the phone to any of the women who had been on that course. And this ridiculous thing that - one of the women on the course was not strictly a union representative. But she was a community activist, well known to some of the other women from Adelaide, and they asked the local TUTA centre director if he would endorse her to come. He did. Well, there was a person on the course who wasn't even a union member.

So, he was in trouble. I couldn't describe to you the rage at that event. It was, it was really tough.

Facilitator: So why did you stay?

Interviewee: That's a good question. I think a lot of us in TUTA would say that when things like that happened to us - it's the management. It's not the people you're teaching. Every day, you're in that training room with people who appreciate what you do. I wouldn’t do it that way again, but I also felt almost like you had to expose yourself if you're serious about a course, you had to expose yourself to all kinds of risks. I had really, really good relationships with the other trainers. My boss at the time, my director, he was - oh god. I'm now involved in a group with him and he's very, very friendly. I forgive but I don’t forget. It's all right working with him in this way but I don’t forget.

And yeah, look, I think a lot of people would have gone with the harassment I got. But it was a job I loved and I was not alone in suffering those punishments either. The male trainers were watched like hawks because it was considered that they were a high risk of sexual harassment. One of them had the most awful experience where he had a - when he taught the union trainer's course, he would ask them to give a talk, a presentation on any topic they wanted that they were familiar with. And one guy was an osteopath or something. He asked if he could do a session on that. It was a woman who volunteered.

She was covered, she was clothed but apparently, she didn’t have any bra on. He put his hand up her back or something. Oh my god. Like the people who were there who said it was nothing. But the trainer who did that was put through so many formal processes. His wife died very suddenly in the thick of it all and I'm sure that there would have been some guilty consciences there. Like there was an obsession with the male trainers to catch them, catch them out doing something inappropriate sexually. So, I guess all of us had our - none of us were the boss' favourite by any means. But we supported each other and people from outside in unions supported us.

And if there wasn't an active feud going on about - well, I had sexual harassment, women's courses, childcare. That was an amazing one too. That was the ongoing conflict that you had. But you could still spend a lot of your time with course participants and with your colleagues and so on. It's really interesting how that all worked. It was a job that was so good, apart from that , apart from that problem. I mean you've got to weigh it up. What else will I do if I do this? If I go back to Sydney, what would I do? What would compare financially. There's something else that I was just going to say but I've lost for a minute.

Oh, yeah. What I was going to say was telling you all of this and telling you what I did and telling you the consequences that it got for me, I learnt to do things in a different way. Like I felt really if I thought there was something wrong, I should just come out all guns blazing saying this is it. We've got to do something. This is what we should do. If you punish me, I'll fight back. I won't walk away. I learnt that conflict isn’t necessarily - it isn’t necessary in every case to win something new. I was just pretty militant I suppose and I went in in that way. And it's a hard way to learn but I think that I learnt a lot about how to raise issues in a way that is - the demand is very clear and uncompromising.

But there are ways perhaps where you don’t ignite all that. I mean I wasn’t involved in the mailout from the women in union training course but if I had my time again, we wouldn't have done that. And that was something where the women were lacking. They were brilliant women. But like to get something in that format to a Labor Council secretary, given the attitude most of them had to feminism and so on, they were just - they wouldn’t learn anything from it. They wouldn’t absorb anything from it. That was just a bit too, too cut and dried as a way to achieve what they wanted to achieve and what they wanted to achieve was really good. It was really good quality stuff.

But it wasn't even that relevant to some of the people they sent it to. Like the Labor Council secretary doesn’t want that stuff. You want that to go to the women's officer or the education officer. Someone who will actually use the lessons in it and apply them in their work. I guess I've learnt - if I've learnt one thing it is you don’t have to make your opponent angry. Like if you can do it another way that's valid, you don’t have to just - this is it. I'm not compromising. If you don’t do it, you're a fascist. You know? Obviously, I didn’t say it in those words but that was the thing.

And I just thought, like I went into the college, I thought well I'm a woman, at last the college has a woman now. I have to fix these things. And it's also now well, do I have to personally fix them? Can I have a group of people around me? Can we do things together? I mean I went in after that total fiasco about the women in unions course, there was a meeting of the directors of TUTA in the college and I asked if I could go in and speak to them about the course. And I came out in tears and that was - I went on my own. I didn’t ask one of my colleagues to go with me. You learn, you learn to do things in a different way if you can do it without compromising what you're after. And I suppose if anything, I learnt that from my time at the college.

Facilitator: One of my questions for you was do you have advice for young women?

Interviewee: For getting into the union movement or generally?

Facilitator: Well, For young women activists, for young women in the union movement?

Interviewee: Right. Well, probably, in view of what I've just said, don’t feel that you personally have to take on everything on your own. If you've got something that's important to you, gather some other supporters around you. Talk it through. Work out what's really important and what isn't. Raise an issue in a positive way initially. If that doesn't get you anywhere, sure, you go into negotiation mode. But you've got to draw on the support of your colleagues, your other women. You need to do things to keep that support group alive too. See each other regularly, have a dinner or something every couple of months.

I have found very important in my work has been building relationships. Building relationships with people who will be honest with you, but will support you generally. Who understand you. So they understand maybe sometimes you're a little bit quick off the mark here. Just slow that down a bit. Oh, gosh, what else? I mean if there's something you can study that will help do it, and in our day, that would have been a TUTA course, perhaps, or a Trade Union Postal course. Or the Labor Council unions NSW used to run this at UPS when it was still an Institute of Technology; industrial law. Two subjects in industrial law.

If you passed, they were recognised in Sydney University, those two units of industrial law. I'd say it’s not for everyone to be studying while working full-time and studying at something really intensive. But if there's something like that that’s been available for people who do work full-time, and you can do it, do it I'd say. It just gives you more confidence. You're more sure of the information and advice you're giving. It was particularly important for me as a trainer because people ask you well are you allowed to do this or that? It's very specific. And I found that apart from my own practical experience in the ASWU, I found that industrial law qualification modules really good.

Really helpful for me. So, what else? Oh, God.

Facilitator: I've got a sort of related question. So, when you started your work with the ASWU, it was a new union, you didn’t have an award. You didn’t have an industry as defined. So, there would be lots of places in the economy now where workers would find themselves in the same situation. And I guess any reflections on your experience that might help if people in those areas are looking to organise?

Interviewee: Well, it's very hard of course because the level of union density has gone down so massively since when I started out. The ball moves very quickly. Like employers are getting more and more creative at how they can employ people not to have to comply with any laws about their wellbeing basically or their pay. And it's really scary, the extent of that now. So, anyone going into that, well they'd be up for a fight. But I think you have to be very clear about what you - that what you believe in is right. Right? You couldn’t do it for two minutes I reckon if you couldn’t say I'm doing this because it is not right that these people have no industrial protection and that their employers have deliberately removed things so that they don’t.

So, you're making it hard for them, you're making it hard for the organisers. I don’t really subscribe to the organising model in any slavish way. But if there are opportunities to talk to those people on their breaks, whatever, to slowly build some awareness. I mean it's overwhelming. You know, sometimes I just think how is this going to end? Union density has gone down heavily and these gig industries, giga industries]or whatever they call them, they're popping up everywhere. How can you keep up? How can you keep up as a movement with this? Although I'm, I’m very happy to see what's happening with the hospo in Victoria.

My daughter is a chef. I have a lot of very strong ideas about that industry as an employer. And they are going great guns. So, they're in an industry where people are too frightened to join the union, who are sacked on the spot, who have no health and safety measures. And that's who they're trying to organise. In one way or another, they're getting those people in. They're running - a very creative idea that I've read about them is that they run a website on your entitlements. They run a website on which employers pay the best. They provide useful information to the workers in those industries and they start the conversation about why you need to stick together.

And it works as well now as it always did, if you do it. I love reading about their disputes where they go and have a rally outside the restaurant. Employers hate it. They hate it. Poor us, you know? You're upsetting our customers by being out there. That is a union that has to take strong action. Because that industry is just a write off across the board. It doesn't matter how small or how large the employer is. It's just dreadful. You think we're sort of swimming upstream. The union density was something like 56 per cent when I first went to TUTA. I remember looking it up.

And you think how can you ever keep up? But it is great to see things happening in an industry like that which is a very, very exploited industry, mainly young people who are too frightened to join the union. I mean I can safely say my daughter, after six years in the industry, has never seen a notice of the award on the wall, a delegate, a member, an organiser. Never ever ever. And they've got an uphill job there. But on the other hand, you're starting to see these big settlements. And that has got to change the employer's attitude at some point. If they have underpaid people to the tune of $3 million or something, like it's got to have an effect eventually.

Facilitator: So, I've kind of got to the end of what I was hoping to hear from you. Is there anything though that I've missed or that you'd like to add with regards to your experience, your career, or reflections on where things are?

Interviewee: Okay. I'll just say one more thing. Just so you have the full picture of my employment. In between going to TUTA and coming back for a year and going back and forth, we had this ongoing thing with my partner where I'd come back for a year. I'd take leave and work somewhere else, back and forth. And in that context, I worked as an organiser in the Administrative & Clerical Officers' Association. Women's organise that. And that's the, originally the name of CPSU. So, I was a women's organiser for two years there too and I had a portfolio of government departments plus women. So that was my other union stuff.

One of the things I'd like to say too in reflections on my experience is that people often say if you work for a union, you'll never get a good job. That's a very prevalent view. Now, I got - after maternity leave - I had my daughter in 1988 and I released that I couldn’t work as a college trainer with a child of that age. So, I actually resigned and came back later. I was there for the end period of TUTA. But having left TUTA, and I was terrified that no one would have me in the public service or anything, I got a job as an industrial relations, human resource manager and policy role with the Office of the Direct of Equal Opportunity and Public Employment.

And even though I was fairly nervous in the interview, because the EEO director sort of had to work with management about policies for the sector. And I was worried that they wouldn’t really give me the job for that reason. And the director, Claire Burton, told me afterwards that the employer rep in the meeting had said well, we're here for the wellbeing of employees and unions are particularly involved in that so it's not an issue. And I mean there’s quite a story that job too. But I found out, I had a research officer - I had a policy officer part time role in the Sexist Discrimin [Discrimination] Unit, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

Policy officer in the research and policy unit at the Department for Women. When TUTA was closed down in 1996, I set up my own consultancy. I just think it's really wrong for people to think that you won't get work because you've got a union background. Because people who have a union background are usually very, very good because they've had to be. They've had to do the really tough stuff and they've had to know what they're talking about. I mean I'm talking about with the Director of Equal Opportunities. That was under the Greiner Government, Liberal Government. So, and similarly with self-employment.

I have found that the work I've done has given me so many skills that are needed. I don’t ever feel that I've been disadvantaged. I think people who want to work for a union but who might want to change later, should do that. Should just do that. And I wouldn’t in any way say that I did the union stuff to enhance my career. But nevertheless, I found to my surprise, that it actually helped a lot. So, that's something to take away. Can't think of anything else really.

Facilitator: Okay. Well I have kept you going for longer than I probably promised, but I wanted to hear everything you had to say. So, I now thank you for that. I'll finish the recording.

END OF TRANSCRIPT