Helen Creed

About this interview

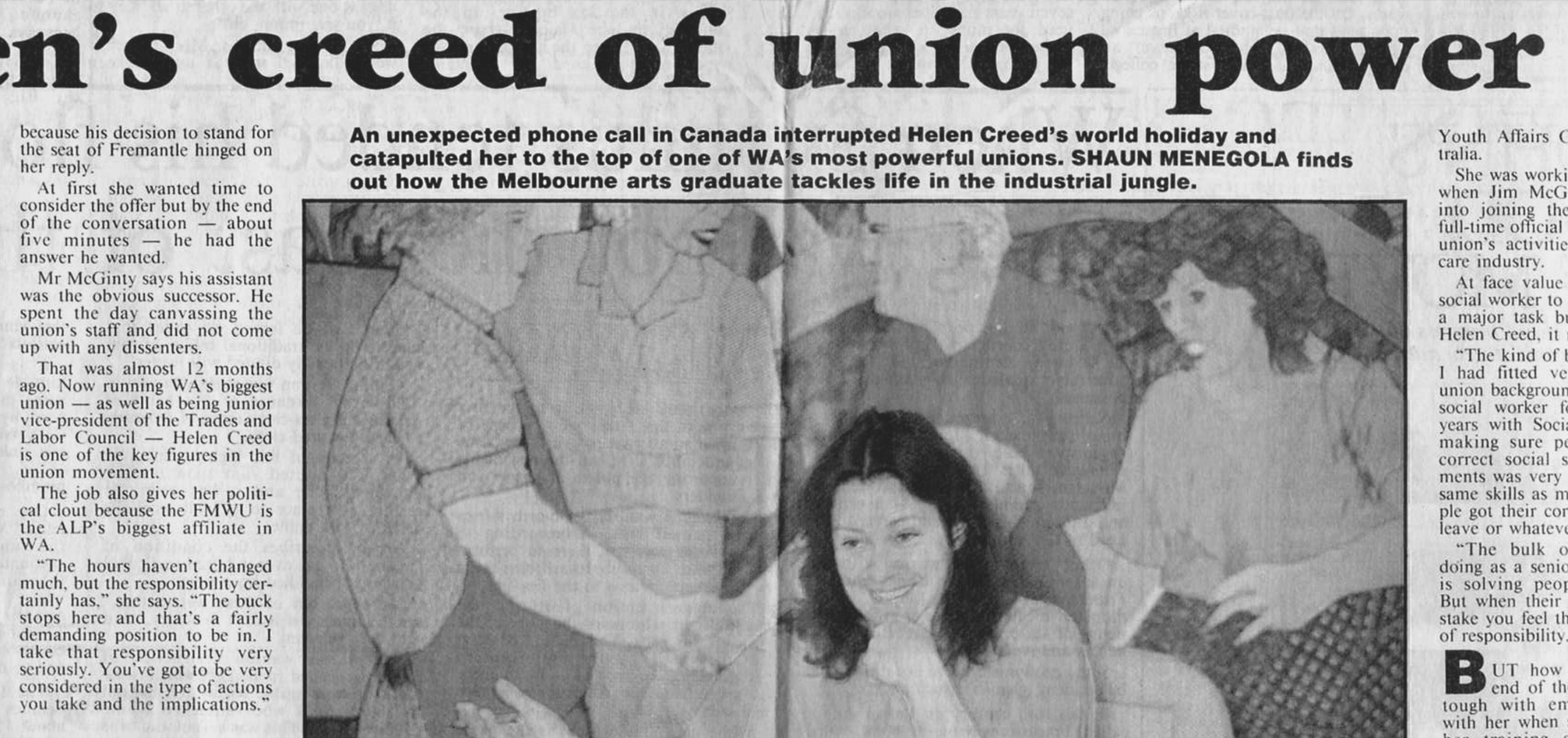

Helen Creed reflects on her two decades of activism in the union movement. She tells us of her beginnings in social work, her transition to leadership positions in the union, and her subsequent return to work in the community sector, where she will always remain a proud life member of the Misso's and Unions WA.

Transcript: Helen Creed Interview

START OF TRANSCRIPT

Facilitator: Thank you so much for sitting down with me this morning Helen to talk about a project that myself and Sarah Kaine at UTS are working on at the moment. We’re trying to capture the voices of women activists and leaders within the union movement over the last couple of decades now.

So, we've been having some really fascinating conversations with a whole range of people, and trying to kind of consider, you know, who are some of the key and prominent activists and leaders that have been in the union movement for quite a length of their careers, but obviously doing other things as well.

That's why I’ve reached out to you to have a bit of a conversation and kind of capture your story of how you got started in the union movement and some of your very different roles that you've had and quite interesting roles in a number of different union-based organisations.

I do have a couple of sort of guiding questions; it's really your story and in capturing sort of your experiences as part of the project, which is really he main thing at the same time.

If we could sort of take it right back to when you first got involved with the union movement. What was that sort of time? Can you speak to me about that?

Interviewee: Yes, I did a bit of preparation before today's interview, and I thought, well, really it goes back to family. My dad was a horse-racing journalist. And he was president of the Racing Writers Association, which was part of the AJA at the time.

So, being involved in things like that, just, you know, was there from the beginning, in a sense. But the Racing Writers Association weren’t a kind of militant union, really. But I come from Melbourne originally, and I went to the school called Murrumbeena High School.

And one of my memories of the school is that the teachers, this was during the 60s, and I think in Victoria, there was a lot of action that the teachers unions took around the lack of funding for education. So, teachers taking industrial action was part of my schooling. That was just accepted in a sense that, you know, the teachers were taking industrial action because of concern over the lack of funding.

And I guess I was then fortunate to be at Melbourne Uni in the early 70s. So, part of that, so called ‘second wave of feminism’. I was doing social work, but very active in the women's movement and the campaigns that were being run then that included the campaigns around equal pay.

And so, while there wasn't a great deal of liaison really and contact, as there was subsequently between the student movement, and the feminist activists on campus, and the women, you know, the women activists through the working Women's Center and that sort of thing initially. It was certainly a very vibrant time, you'd have to say around broader social action.

So those early days, I think, were quite influential. And I moved to Perth in 1977. And as a social worker, the professional association was the Australian Association of Social Workers, which I've actually never been a member of, I'd always been a member of the Australian Social Welfare Union.

And there was quite a split, you know, there was the professional association and there was the ASWU, and certainly in WA, the ASWU was fairly small. And it was really where the activists kind of gathered in that I, at my first job in Perth as a social worker was in the Department of Social Security.

And so, I was a member of the relevant union, which was the Commonwealth, I think it was called the Public Officers Association or something like that. So, I was a member of the union in my workplace, my activism was really in the ASWU, and that brought together I guess, a range of social work activists in WA.

And the ASWU did take up specific industrial issues. But as I say, most of the people who were there who were members were there because of the broader activism than the kind of traditional union reason, if that makes sense. And my first job in the union was as the childcare organiser for the Misso’s. I still think that as the Misso’s it's gone through a considerable number of…

Facilitator: Yeah, that’s it.

Interviewee: changes, but in WA it was always called the Misso’s.

I had been working in the childcare sector. I was the national president of the Youth Affairs Council of Australia. And so, I hadn’t actually been working in a regular job that year. I’d been trying to study but that wasn't very successful.

And the federal and state governments had put a lot of money into childcare after the elections in ‘83. And in WA we set up what was called the Childcare Planning Committee. And that was a very well structured mechanism for increasing community-based childcare services.

And a close friend of mine was the CEO and she had employed someone as a community worker. And they basically rung the morning they were due to start to say, I'm sorry, I'm doing something else. And so, she was left in the lurch. As I say, I wasn’t working in a regular job, I was traveling over east because I was national president of YACA.

And I said, well, I, you know, I can do it. So, I stepped into this role. And it was in that role that I had quite a lot of contact with the union, because what the union had done here in WA was the Lady Gowrie Centre which there's a Gowrie in each state that was set up back in the 40s named after the Governor General's wife, that was here in WA was really quite progressive.

And they had approached the union and said this is very uncomfortable for us that we have these workers who are all working together, but we've got teachers who were being paid teachers wages and 32 hour weeks and 11 weeks annual leave, we've got qualified staff who are being paid, again, as qualified, not highly paid. But they're working 37 and a half hour weeks, and six weeks annual leave. And we've got unqualified staff who are working 40 hours a week, and get four weeks leave. And we want to standardise those conditions where we'll keep the wage rates.

And so the WA branch had negotiated an award with the Lady Gowrie that standardised conditions. And what we did is apply that award to the first three centres that were established under the Childcare Planning Committee, under this new funding. And so I had quite a lot of contact with the union in putting that in place.

And towards the end of 1984, I was approached by the then president of the union, who was actually one of the teachers at the Gowrie, and the Secretary of the Union Jim McGinty, who said that they wanted to pick my brains around who might be around in the childcare sector, because they had a vacancy. The previous childcare organiser had gone on maternity leave [and come] back to work and once her daughter was a year or so old, she was just finding it too difficult. And they hadn't been able to fill the position.

So, I just took that request for what it was. And partway through our lunch Jim said to me, ‘Well, what about you? Are you interested?’ And I went, ‘Well, I’ve never thought of working for the union before. But, yeah, I'll kind of give it a go.’

And so, I started in the beginning of 1985 as the organiser for child care and that also covered teacher assistants. And so, I think, for me, that was a kind of, in a sense, quite an appropriate way to get involved in the union, because it was about an issue, you know, that the union played a role beyond wages and conditions in relation to child care, it was very much part of the sector, it was a voice for the sector.

My social work background really fitted into that very well and a long term commitment around community-based children's services, an interest in policy. And so, the union really had quite a significant policy role.

And I think being in the WA branch of the Misso’s, at that time, there were more women officials in the Misso’s WA branch than the rest of the union put together. So, it was a very different branch than some of the other branches.

And it was also… people talk a lot about Bill Kelty and the ACTU’s amalgamation. Well, Jim McGinty was the architect of a merger in WA some years before that. And so, the Misso’s union that I went into was an amalgamation of the Miscellaneous Workers Union, which was a whole lot of very small manufacturing kind of areas, the cleaners and caretakers union, the hospital employees union, the water supply union, and the preschool teachers and associates union.

And so, you had this amazing range of occupations and many, you know, if you contrast it, for example, with the Victorian and New South Wales branches, the basis of their branches were the cleaners. Whereas in WA, the largest part of that merger was the hospital employees.

And it was across the board, hospital employees, cleaners, caterers, orderlies, and enrolled nurses. And it was interesting to read some of the minutes of the meetings of the preschool teachers, for example, who were debating them as teachers going into a union with water supply workers.

But it was, as I say, I think the vision that Jim and Owen Salmon had in terms of bringing workers together into that strength, you know, unity as strength. And Jim actually commissioned a history called ‘From Fragmentation to Unity’ about those amalgamations.

And so, there was a broad range of industries. There was that political undertone that that these were Left unions. And so, the Misso’s was one of the significant unions on the Left. But as I say, was that was the kind of union environment that I went into.

And I just thought, you know, all unions were a bit like that. Particularly, I was, I guess, surprised when I discovered, as I say that the number of women, and that had come from of the five amalgamating unions, two of the Secretaries were women, the cleaners Secretary and the preschool teachers Secretary.

And so they had a number of union officials, but it went back to, for example, Jim employed Pat Giles who became one of my key mentors. Because in the health union, they were trying to get into the private nursing home sector. And as he described it, he wanted someone who could go ‘bosom to bosom with the matrons in the nursing homes’. And so, Pat was employed.

And so, she was the first woman employed in the Health Employees Union in the 70s. And she went on to be active at the ACTU and that sort of thing before going into parliament as a Senator. So, as I say there were quite a lot of very active women who were in the union. And that's what I went into as a young official.

Facilitator: That’s interesting. Yeah. And so much to unpack there. Yeah, thank you, Helen. You mentioned a bit earlier in terms of the women's movement and some of the campaigns around equal pay and things like that, that we can come back to as well.

But I'm wondering as well, in those sort of early days of being within the Misso’s Union, is there a key issue or key campaign that you were involved in that sort of really stood out as quite significant or important during your time there?

Interviewee: I guess, the particular campaigns I’d want to most talk about were during the 90s.

Facilitator: Yeah, yep.

Interviewee: But perhaps to share a kind of funny story my experiences as an organiser. The childcare and teacher assistants sector was not seen as a very militant sector. But we had very high coverage among the teacher assistants who worked in what were then called the special schools. So, schools that were particularly set up to cater for kids with disabilities, a range of disabilities

And the teacher assistants were, as part of the campaign for better wages, we were talking about potential industrial action that could be taken. And as I say, this is not something that was you know, very common across that sector.

And the teacher assistants in the special schools, that are now called education assistants, they came up with this campaign that they would refuse…one of the things that they were doing was the laundry and actually taking the towels and things home and laundering at home, and that they would stop doing that.

Now that was seen as quite amazing for these women who had never taken industrial action before to take that sort of industrial action. But it was, I guess, because so many of the workers, members of the union, it was something like 75% were women workers. And so that sense and that sharing across the, the union of taking action was something that, I guess, were certainly led by the cleaners, were certainly led by the hospital workers. But it did kind of, in a sense, filter through to the others, because they saw women standing together taking action.

And I guess, there were some fairly significant picket lines in those days that people used to comment about the Misso’s picket lines, that there’s always such good food on the picket lines because we had a pretty multicultural workforce.

And people would bring food, because that's in a sense what women do together. And so, yeah, they're just a couple of memories there. But I guess, as I say, it was the 90s, where most of the significant action that I would talk about.

Facilitator: Yeah, Fantastic. Fantastic. Thank you, Helen. And, and with that, as well, now I'm wondering if you can share with me what other sort of roles you then took on within the union movement. And I guess what sort of inspired you or motivated you to want to move to more of a senior level within the union movement?

Interviewee: I guess I should share… I had only been in the union for a couple of years in 1987 when Beryl Baker who was one of the two assistant secretaries left, and there was an election for that vacant position. And it was between myself, who was seen as a young female academic, didn't come from the shop floor, as opposed to an older male shop- floor delegate. And it was quite a contested election.

And in the end Stan had the numbers on the executive. I was supported by the Secretary and the President. And one of the other older people who would have expected in a sense to support Stan said to me, Helen, I'm supporting you because you are the future for the union.

So that was quite a significant election. The following year, the other Assistant Secretary actually was appointed to the Commission, and I was elected unopposed. And so, I think, people were kind of critical, in a sense, because of seeing that long-term commitment to the union that was through being a delegate being on the State Council, that sort of thing, as opposed to someone like myself, who was coming in with a long-standing commitment to social justice, but just not through that activism in the union.

And so I think that's quite a critical issue for women, particularly, you know, I'm talking in the 80s, women coming into the union, and I think a number of us came in from that sort of social justice background.

But what was interesting, I think, also then being the Assistant Secretary, that was at the time when affirmative action was being discussed, and there were affirmative action positions on both the Trades and Labour Council and the ACTU.

And I was elected onto the TLC Executive in an affirmative action position. And the ACTU election, the Left position, there was an expectation that someone, a woman from Melbourne or Sydney would be elected into that role.

And there are a group of women outside that Melbourne/Sydney axis who said, well, no it’s about time someone else. And so, because I was an affirmative action person already, I was Assistant Secretary, and there weren’t that many elected women union officials,

I put my hand up and I was really supported by other women officials from the non-Melbourne/Sydney states outside Victoria and New South Wales. And women like Steph Key, who is still a friend. She, you know, she contacted me and said that the women in South Australia were keen to support someone outside that Melbourne/Sydney kind of axis.

And so, there was a bit of a steamrolling kind of, or a gathering of support and of course I did know a number of officials in Melbourne and Sydney, obviously through the Misso's, but also people like Brenda Forbath who at that stage was the key childcare person at the ACTU.

So, I was actually elected onto the ACTU executive in that AA role. And that was, as I say, quite significant because it was someone outside that main Melbourne/Sydney axis.

Interestingly, when I was elected Secretary in 1990, I stepped down from the AA position at the TLC, I said affirmative action is about giving women the opportunities that they wouldn't normally have. I said, I'm now secretary of one of the state's largest unions. And by that stage, I was the third affirmative action Vice President.

And I said I should be elected in my own right. So, I'm not going to stand as affirmative action Vice President. I didn't. And so I didn't get up, but I was subsequently elected the following year as one of the vice presidents, not as the affirmative action Vice President.

And I think that's really important in terms of the role that affirmative action played in the sense of women being able to take those positions. And you know, that area of affirmative action I was one of the founding members involved in Emily's List, which again was set up after the rule changes in the ALP in the 1994 conference, because we realised that you could change the rules, but you never changed the culture.

And I think the experience of women in the trade union movement, where we went from the position of having Jennie George elected in 1983 as the first woman on the ACTU executive to having Jennie elected as president, you know, within such a relatively short period of time.

That it was the women's experience in a sense of affirmative action within the trade union movement that was a very significant driver of those changes in the Labor Party as well.

Facilitator: And can you just describe Emily's List?

Interviewee: So, Emily's List was based on an organisation in the United States called Emily's List and Emily stands for Early Money Is Like Yeast. And it was initially established to assist democrat women who were pro-choice with financial backing because, as you know, in the US, it's really, really expensive to run for parliament.

And so it was very targeted around choice. But what happened is the organisation as it sort of established, provided mentoring and networking and training for the candidates as well as money.

And one of the Victorian ALP women, Leonie Morgan, had been to the US, and she came back and talked about it at an ALP women's conference. And initially people were a little bit lukewarm.

But after the rule changes in ’94, as I said, we realised that if you were going to change things, it wasn't enough to just change the rules, you had to change the culture. So, we set up Emily’s List as a… initially we were looking at setting it up within the ALP, but it became obvious fairly quickly, that some of the key men within the ALP were not going to allow the women to run the show.

So, we set it up outside the ALP. And it was launched in at the end of 1996. And myself, and Joan Kirner, the former Premier of Victoria, were the original co-conveners of the National Committee. And so it was set up with a National Committee of two women in each state and territory and immediately got involved in fundraising for candidates.

Emily's List stayed out of pre-selection, still does. It’s once women have been pre-selected they are, well many of them are Emily’s List members to begin with. But those who aren't are approached if they want to be part of Emily’s List. And the significant issue is a commitment to choice, to pro-choice. But when we first established Emily's List, we said there are four pillars: there’s choice, but also childcare, equal pay, and equity and diversity.

So again, you can see for me, that childcare, equal pay, it's the kind of constant sort of underlying commitment there. And so Emily's List has been involved in…I can't off the top of my head know the numbers, but most of the women parliamentarians, Labor women parliamentarians are part of Emily’s List and have been supported by Emily's List in Parliament's today.

And Emily's List had also been a very strong advocate within the Labor Party of affirmative action rules and changing those rules from…like we did in the union movement when the first rules were put in place it was about 25% women on the executive and then move to 35%, then 40%, then 50%.

And so, the, as I say, the history and the involvement of the trade union women in Emily's List, the prominent trade union women from, you know, people like Jennie George, Sharan Burrow, Wendy Caird and others were involved initially in the union movement, but also then in Emily's List as well.

Facilitator: I'm wondering if you can you share with me, Helen, what was that experience like, you know, taking on issues such as affirmative action at that particular point in time. And I know, you've mentioned the sense of rules are important, but culture is also important.

Was there any resistance you sort of faced in kind of driving those sort of issues? Or what was that sort of experience really like for you?

Interviewee: Oh, the experience in negotiating the affirmative action rules was pretty much similar to my experiences as a secretary, as a woman in the union movement. I mean, when I was elected Secretary in 1990, the CCI actually coined us as the ‘Ms’-cellaneous Workers Union, because we had a male president, myself as secretary and two assistant secretaries, one male, Stan, the person I mentioned earlier, and Sharryn Jackson.

And so, people saw us as female-dominated and all of this sort of stuff. Whereas in fact, as I say, the majority of our members were women. And so we we're reflecting that in terms of having a woman secretary.

And when I was elected, people thought I was the first woman to be elected secretary of the Misso’s. But one of the journos who worked with us, he actually did our journal, he looked into it and he discovered through the archives, in Canberra, that the first woman secretary of the Misso’s was actually a woman called Florence Anderson, who was Secretary of the Victorian branch during the 40s.

And she was a teacher who'd been forced to resign when she got married. So, she was working for the union. And it doesn't say what happened. But she stepped down in 1946. So, whether she was someone who was pushed out when men returned, or whether she just retired, there's nothing in the documents that Bob was able to find that indicates that.

But I think it's really telling that that was Florence Anderson in the Victorian branch in the 40s. I was then the second woman secretary of the Misso’s. And after that there was just a series of women elected into Assistant Secretary, Secretary, paid president positions. So now every branch has had women in leadership positions.

So it really is that significance of not just making a change individually, but changing that culture and seeing that women were in that leadership position. I mean, it didn't come without its frustrations and attacks.

One of the male officials I employed, had previously worked, I don’t know if I should name the union, but….

Facilitator: No need to if you don’t want to.

Interviewee: He worked previously for the Transport Workers Union, he'd been overseas, he'd come back, and I didn't know him, but others did and so I employed him.

And he said that he had bumped into some old comrades from the union and they’d asked him how was life at the coven. And so, he came back and told us. And I think one of the important things and one of the things that kept me sane was the group of women who were officials in the health area of the union, who used to be called the health hussies, they bought me a witch and this was a toy witch that sat in my office and rotated in the air conditioning.

I was also accused of being a witch by the Secretary of one of the Right wing unions who, we had an official… the health servicesunion dealing with health, you know, the social workers, the OT’s, the physios, etc. They were replacing their Secretary. And because of my involvement through the health sector, I knew the president of the union who was a physio at one of the major teaching hospitals.

And I talked to her about one of our officials who was an ambulance paramedic, that's how he came into the union and he was Secretary of the ambo’s part of the union and that he’d make a very good secretary.

And so yeah, I lobbied her, and he was actually appointed to that position. Now they were a Right-wing union. And as I say, the Secretary of one of the largest Right-wing unions accused me of bewitching the committee. So, you know, that was just par for the course, that kind of criticism.

One of the others was we had a picket line at Sir Charles Gairdner hospital and that was…at that stage they had a supply chain that meant the sort of target, if you like, of the picket line, was the laundry coming in and out, the trucks.

And so, I had done, as you do during picket lines, a TV interview on the picket line. A couple of days later, one of the Liberal Members of Parliament attacked me in the Parliament, not just because of the strike, and the disruption it was causing, although we had patients on picket lines, because they could see it was about, you know, quality of care, as well as wages and conditions.

But anyway, at one point, he said, that I was a disgrace and that I should have the decency to do my hair before going on camera, because I looked more dishevelled than the dirty laundry.

So people, friends who are in the parliament, at the time…it was a bit of a fracas around that, and so they sent me the Hansard. And one of our officials who was actually on leave, got to hear about this. And in the mail one day turned up the Ross Light[foot] survival kit. And when I opened it, it was a hair kit, it had one of those brushes with a mirror and some clips.

And that's what I say, that sense of humour was really very important to me. And that sense of solidarity and support that I had from the officials who were around me. We were seeing that we were the voice of low-paid women workers. And that was really important to be doing that.

And so, you know, the kind of crap that you had to put up with what's just par for the course really. But I was able to put up with that because I had that support across the union from the men and women who worked in the union, from the members of the union. So yeah, as I say, I think that was just certainly par for the course.

And it has stood me in good stead, because, you know, I'm used to being in situations where you're the only woman in a meeting, you’re the only woman in a room. But as I say, I had a feeling that I was seen as the voice of low-paid women workers. And because many of those workers were in areas where they were reluctant to take industrial action, we had a very clear media strategy. So, it was about going through the media to the people who were impacted by the services our members we're providing. And so, as I say, it was very much the Misso’s seen as that voice for low-paid women workers.

Facilitator: It's very interesting. And I guess that's something that I was curious to kind of understand about your journey and experience as well, Helen, but getting that sense of what are some of the biggest barriers or challenges you've faced in actually trying to do the work that you're doing within the union movement?

I know that you've had a range of different roles and various kind of senior roles. But can you give me a sense of what you sort of see as some of those major challenges you really faced to doing your actual work as a union officer and an activist?

Interviewee: Well I think…I mean the challenges, obviously, were there, but I never give up, and I think that's really important. I mean, I say to people, I've been a member of the St. Kilda Football Club since I was a kid. You know. I never give up. I'm always optimistic that we’ll get there. And I think that is how you do overcome the challenges, that you just, you just keep going.

But you're surrounded by people who support you in doing that. You know, the changes in the union movement, for example, at the ACTU level were…and Jennie George, I know you've interviewed Jennie George and I'm not sure if she shared this paper with you that she presented at a conference. But she talked about the four key things that led to the changes. And if she hasn’t, I’m happy to send it to you. I think it's really significant that it was about…we had clear supporters, and so Bill Kelty was a supporter of affirmative action, because it was about the survival of the union movement.

If you didn't have women members, then the union movement wouldn't survive. And the proof of that is in the pudding today, where there's now a higher proportion of union members are women. And it's exactly what indigenous people are saying, particularly, you know, getting some publicity during NAIDOC Week. You can't be what you can't see.

And so, what leaders like Bill and I, I would say leaders like Jim McGinty here in WA, was saying if we want women to join the union, well, then they've got to see women in these leadership positions. And that is really important.

The other part of it is we had a clear strategy. Like we didn't go for broke at the beginning. We had a clear strategy, we had a clear plan. It was incremental. The women who were involved, we're all leaders in our own right. So, you couldn't dismiss us because we were Secretary’s or President’s or whatever. And so, the women leading the charge were women leaders.

And we were backed by, you know, many women standing behind us. And so, I think those sorts of things, the challenges, yes, were there, but I think what I remember I guess and what I reflect on, is how we met those challenges and those, those key things like having key supporters, like having a plan and a strategy, having the support of other key women are all part of what was my experience then and ever since really.

Facilitator: Absolutely. And I'm wondering if you can share a bit more with me, Helen, about what it was like was working in some of those other union organisations like the ACTU and like, Unions WA as well. And I guess sharing some of your experiences, having quite senior roles within those leading organisations within the union movement and what that sort of experience was like, and what some of the key issues you were dealing with at that kind of level?

Interviewee: Well, I think the most significant really was the 90s and the introduction of the anti-union legislation. And we had seen it coming from New Zealand, where New Zealand had introduced individual contracts. And so, through the TLC, as it was then, in WA, we had actually bought over a couple of activists from the teachers union, and from the equivalent of the Misso’s: the Service Workers Union.

And I remember taking Mark Goshe, who was one of the union leaders who came over, down to CSBP, which is a large fertilizer works south of Perth. And he was standing at the back of a ute, addressing…and the workers, we weren't allowed on site. So, the workers had all come out. And this was a workforce, not only Misso’s, but all the various trades as well.

And so, Mark talked about what had happened in New Zealand and what the Conservative Government was doing and the impact. And he said to me afterwards, he said, ‘I'm just blown away that workers in Western Australia would be prepared to, you know, walk off the job to come and listen to me’. And I said, ‘Well, that's because we're worried. We're concerned, we can see this coming’.

And I think that was one of the characteristics of that industrial legislation, that in WA we were prepared to look around the world, see what was happening. And we had what was called the ‘first wave’, which was not long after Richard Court, and Graham Kierath and Graham Kierath was [elected] the industrial relations minister. And he had said in Parliament, that what got him into being a parliamentarian was the union and his experiences with the union, the Misso’s, because he was a contract cleaner. And so that drove him.

And workers in industries, like contract cleaning, bore the brunt of those changes, and individual contracts were one of the key aspects of that where particularly in an industry that is competitive, and where the major cost is labour. So, the only way you can compete is by reducing conditions and wages. And that's what we saw happen in that first wave.

I think one of the other things was the power that unions had been used to having members have payroll deductions. And in many cases employers actually signed the workers up into the unions. And so that…I mean, we lost something like 13,000 members overnight when the government decided to stop payroll deductions. Fortunately for us, Kennett had done that first in Victoria. So, we learned from our comrades in Victoria how they had tried to address it and what they had done in terms of getting people on direct debit, getting members on direct debits.

But that was a very significant blow to the movement overnight, just no payroll deductions. But I think what's really interesting and what is important is that, for example, in WA when Labor got re-elected back in 2001, they offered the union payroll deductions and we went ‘No. no thanks’. Because (a) we didn't want to put ourselves in that financial position again. But also, there's some benefits of not having payroll deductions in the sense of that connection you have with your members directly, but also that for many of the industries that we covered, people move from job to job. So, if you're relying on payroll deductions you often missed out. Whereas if people are on direct debit, then their union fees continue.

But at the time, that was really a key attack on the unions. And then we had the second wave. And then we had the third wave. And the third wave, really was, the most significant, I think, in the sense that in WA, the political system is that regardless, we've now got fixed terms, but then we didn't, and regardless of when the election was, the members of the upper house didn't take their seats until May.

And the election had been, I think, in December, but the government had lost the numbers in the upper house. So, the third wave was about introducing the…the basically the range of things that they still haven't done. And so, we had this view as the, as the senior members of the trade union, that we needed to do something to get it back in people's consciousness.

And so, we did this blockade of the freeway. And it was something that was really well planned in that we basically just all drove on to the freeways, these key freeways in Perth, and slowed down. That's all we did. But we had two or three cars behind each other, and we slowed down. And of course, as you know, you have the morning traffic reports, and there was this great buzz going around about what was happening. And because then you put out the press release, this is why it's happening etc.

And we had a huge rally at Parliament House to protest against this. And one of the things that we decided to do was that we wanted to have a kind of presence there at Parliament House. And we tried to get a caravan and we were not given permission to have a caravan there. But someone came up with the idea that well it wasn't a caravan, it was a first aid post.

And because we had so many people there, thousands and thousands of people, we needed a first aid post. So, after the rally, the Misso’s, as the health union, staffed the first aid post, and that night the cops came to move us on. And we were able to let people know very quickly, this is pre-social media. But we did have mobile phones in those days. So we let people know, and a number of people gathered and someone had the foresight to let the air out of the tyres.

So the cops moved it off the grounds of Parliament House across the road to what was vacant land. And that's what became Solidarity Park. Because one of the officials had the knowledge around the mining legislation that you could peg it as a site. And so, we actually claimed that as Solidarity Park and that was the symbol for months and months and months of resistance. And unions took it in turn 24 hours a day, each 24 hours to staff it And so it was a site of a lot of activity. Tour buses used to drive past to show this is Solidarity Park.

And so, it was staffed 24 hours a day for about six months. By that stage, the legislation had gone through. We occupied Parliament House, we occupied the chamber. And there were about 30 union officials who did that the night the bill was being debated. And all we were doing was trying to make noise and so that they couldn’t debate it. And people gathered and so we had thousands of people outside Parliament House that were a ring right around Parliament House as the legislation was finally passed and it actually had to…they moved the chamber. They left that chamber went into another chamber, another room to pass the legislation so that they could have that legislation in place before the composition of the upper house changed in May.

And I think it's genuinely acknowledged that that campaign, the first wave, second wave, third wave campaign, the sum of the things that we did, you know, the WA union movement, like many of the others, have always had a choir, Bernard Carney who was our choir Master, but also he penned a song for each wave. And so, when you have thousands and thousands of people all together, singing, you know, we will all stand together and sing a union song. It's very powerful.

And so, we didn't have the kind of disruptions and violence that you saw in some of the other disputes later on. And that was attributed to the fact that we were doing it by things like having people singing, we were doing it by having women in the front line, kids in the front line, community with us. So, all of those disputes had a very diverse group of people.

And it was seen not only as the forerunner to the disputes around Workchoices that subsequently came in at a federal level, but also for the MUA dispute. Because it was that community involvement in the MUA dispute that was one of the critical aspects of that.

And so, for us in WA, we went from the third wave dispute, to the MUA dispute, to the Workchoices dispute. And I think for many of us, it just felt like you were constantly kind of out there campaigning. But it was also a time where unions were very much together.

And the leadership of the union movement throughout that time, the Secretary of Unions WA, Tony Cooke, Assistant Secretary was Stephanie Mayman, Keith Peckham was the President, I was the Senior Vice President. So, we had women in prominent positions, we had women, you know, on the picket lines in the front line.

And I guess one of the examples of that was during the MUA dispute, and we're all down there, and it was sort of two o'clock in the morning or something. And this bunch of guys were sort of, they decided that they would form up and march down the road.

And there was a group of us women who kind of went ‘oh, you know, bugger this, let them get on with it.’ And so we went to get a cuppa. That was the night that the police came over the fences. And so those of us who’d kind of let the blokes do what they wanted to do, and you know, with that bit of aggression, we turned around and saw them coming over the fences. So, we all ended up on the front line and got hauled off into the paddy wagons and that sort of stuff. But yeah, as I say, there's those kinds of examples where you see that kind of macho stuff. But it was very much women very actively involved throughout all of those disputes.

Facilitator: Wonderful. That's very interesting. And I'm also just conscious of your time as well, Helen. And I just have a couple of extra questions if maybe have about 10 or 15 minutes.

Interviewee: Yes, absolutely. No problem.

Facilitator: Yeah. Wonderful. The question I have sort of touches on some of the things that you've just been answering that question there.

But I'm curious if you can sort of unpack for me how the external environment has really shaped your own union work and action. And within that, I mean things like, you know, different politicians coming or going, or you know, what the government sort of landscape is at any particular point in time and the political landscape. But how has that kind of influenced your responses or your union work as well?

Interviewee: I think it's really just a matter of being really clear about what you're doing and where you want to go. And as I say, what was particularly, throughout my time at the Misso’s, driving me was this was about improving the lot of low-paid women workers.

And we used to have quite a lot to do with our sister union in New Zealand. And one of the officials there, she'd come and given a bit of a training course for us. And her message was essentially, yeah, you can't rely on the legislation changing. You can't rely on the politicians. You can't rely on these various external factors. You've actually got to focus on yourself, the union, build up the delegates, you know, build up the membership. It's what you do, is the critical thing.

And I think that is what really epitomized that like, as you know, your question in terms of, well, there were all these various things, and sure it made a difference, it makes a difference if you've got Labor politicians who aren't going to privatise services, or Labor politicians who bring services back in-house, once they've been privatised. Yeah, I don't want to dismiss those and the importance of those kinds of actions. But equally, you can't rely on those.

It's really about what is at the core, and what is at the core is the wages and conditions and lifestyles working, you know, working lives of low-paid workers. And because they're low-paid workers, it tends to be they say it’s women workers, its workers from a whole diversity of backgrounds.

And so that's been, I guess, my privilege to have that kind of membership that have been the driving force for me. But throughout as I was thinking, with Emily's List, my early involvement in the 70s, as a feminist was around issues like childcare and equal pay. Well, childcare is still one of the things I’m most involved in. So, I guess it's a consistency of those issues as well. And to me at the heart of that is social justice.

Facilitator: Yeah, absolutely. And I guess that also brings to mind one of the questions I wanted to ask you about your experiences, but how have you sort of seen during your time, and I guess that the length of time you've been involved with the union movement and now doing other things as well, but how have you sort of seen the issues or challenges facing the union movement change or over your time? Or maybe they've stayed the same? You've touched on a couple of issues. But what's that kind of perception been like for you?

Interviewee: I think the change, or one of the key changes that I've seen, is back in the 80s, and part of my role as ACTU Vice President, one of the Vice Presidents, was I chaired the Women's Committee. And so, the issues that we were raising that were of concern to women workers, things like childcare, but they were things like part-time work, they were things like work family responsibilities, they were things like casualisation of the workforce. What we saw was those then became mainstream union issues.

Casualisation of the workforce is one of the most significant issues facing us today. But back then they were seen as women's issues. And so, I think that's one of the most significant changes that those issues that we were campaigning on in those days, going back to the 80’s, which were seen then as women's issues, that are now seen as worker’s issues. And casualis ation I think is a classic example of that.

Facilitator: And with your experience as well, I guess I'm trying to get a sense of, through your journey and the different roles that you've had, which is very impressive, has there been kind of capacity to sort of balance other things in life as well or I’m thinking of that concept of work-life balance. Has there been that sort of capacity to appreciate other aspects of life, whilst, you know, you've been involved in a lot of different issues and different campaigns over your time?

Interviewee: Yes, there has. I have a very supportive partner. We don't have kids, but I do have a goddaughter I'm close to. And I guess because of the opportunities I had to be in, particularly in Melbourne, and I would always stay with one of the… well, we shared a house together when we were at uni. So, we've been friends for a long time. I've grown up with her three daughters. And so, I would always stay with her when I was in Melbourne. I think if I had to stay at hotels, I would never have done the amount of involvement nationally, because I also used to stay with my sister in Adelaide. So that's part of it.

As I said, I'm a mad keen St Kilda supporter. So, for a number of years, I was president of the Western Saints, which is the St Kilda supporters group here in Perth. But I think there's two things perhaps to say. My partner and his family, well him in particular, really wants to be a farmer. And so, we've had a farm, which is a real farm, not a hobby farm in the sense, and the thing about the farm is that because I'm a city girl, things that he would see as just, you know, normal, I would actually have to concentrate on. So, if you're standing in the middle of the cattle yard, trying to sort cattle, you can't be thinking about work. And so that ability to have that opportunity to cut off was, I think, really very critical.

And because I had the opportunity to travel particularly to Melbourne and Adelaide and maintain those kind of relationships, close relationships with people who were really important to me, was also critical. Because Western Australia can be fairly isolating. You know, like, when my dad died, there was a plane strike. So, you know, I couldn't get back. I mean, it's nothing in comparison to what people are going through over the last 18 months with COVID. But, you know, you really did feel quite isolated here in WA.

And I think the other thing is, I've always got inspiration from stuff happening internationally. So, for example, in 1995, I was part of a work brigade that went to South Africa. So that was not long after Nelson Mandela was elected. And we were working with the ANC and particularly the women's committee of the ANC. And most of their structure had been decimated as they had all been elected into parliament. Because not only was there the Federal Parliament, but there were all the provincial Parliaments, and they had at least a third women on every ticket, and you had some of their provinces where the ANC one, I think one province it was 90% of the vote. So, the entire ANC women's structure, basically was in Parliament.

And so, we were able to, you know, provide some really practical and useful assistance through that work brigade. And one of the things for example, was Thabo Mbeki had come to

the women's committee, the ANC women's committee, with legislation that had been drafted around equal opportunity. And myself and one of the other people on the work brigade, Cheryl Davenport, who’d been a member of parliament, the two of us were asked by the women's committee to go through the legislation and make sure it was kind of okay, like, raise any issues.

And so, we did that and when we're talking to some of the ANC women about that they said, you know, this is amazing, because we've had absolutely no experience of government, no experience of legislation. So, we would not have been able to identify these kind of things. Because it was just completely outside our experience. And they were concerned about being snowed by the bureaucracy really, that would capitalise on the fact that they didn't have that experience.

So, we were able to do some, you know, things that were actually quite useful, based on our experience. And I have had the privilege through the union movement, I mean, that was a personal thing, but certainly through the union and involved in the international union work. And again, just happened to be in the right place at the right time, in the sense of it was the Asia Pacific’s turn to have the chair of the International Women's Committee.

So, I chaired that for four years and that gave me a range of different experiences and opportunities from, you know, meetings with financial institutions and all sorts of very senior international bodies, to things like, SEWA, which is the Self Employed Women's Association, which is an amazing organisation in India, that pulls together from the women's movement, the cooperative movement and the union movement. And they had applied to be a member of the international trade union movement. And it had been opposed by the unions in India, the existing unions, because they said they weren't a real union, because they didn't take strike action.

So, we had a mission to India to look at what SEWA did. And the General Secretary…we were with a group of women SEWA members, and the General Secretary said to them, ‘Well, can you tell me what you do? And what SEWA as a union has done for you’. And one of the women said, ‘Well, my job is picking up iron filings off the floor. And what SEWA has done is provided me with a magnet. And not only does that mean I could pick up more iron filings, but it means that I don't have to be bending over the whole time’.

And so, we're all in tears, because that was the impact of the union. So needless to say, it was a unanimous decision that SEWA should be a member of the international trade union movement. I've been working on a project that got derailed by COVID, but I'm certainly still working with SEWA through a project that Sharan Burrow, the current international union movement Secretary, had asked me to get involved in around childcare.

So yeah, as I say, I've had the opportunity to be involved at that international level. I led a solidarity delegation to East Timor before the vote, the independence vote. I led a women's delegation to Israel and Palestine around peace. So, the inspiration that I have been privileged enough to get from international stuff, again, has been really important for me. It's what inspires you. And if you're inspired, and you’re backed by people. I mean, it's that that inspiration and the solidarity and sisterhood. They’re the two things that I would say just keep me going.

Facilitator: That's a fantastic story. That's a wonderful example. I guess reflecting as well I know, we've talked about a range of different insights and experiences that you've had, but I'm wondering if there's perhaps a key moment or a moment or two or something that's very enduring in terms of what you sort of take away as being most significant about your long journey within the union movement. And I guess in terms of a memory you've had or say significant touch point you've had during your time with the union movement?

Interviewee: Oh goodness, there’s been so many. But I guess one of the things is, as I said, the 90s and the industrial changes and the attack on workers, and particularly around individual contracts. And I remember there were two cleaners, two women cleaners who, and I just can't remember where they worked, but after the change of government, and individual contracts went, and they were re-employed as permanent workers, permanent part-time workers.

And the West Australian, which in those days was always so anti union, their front page was this photo of these two women with their mops. And that's an enduring memory for me and I think the headline was ‘we've won’, or something like that. But it was just epitomised what that was kind of all about. That here you’ve got these two women cleaners on the front page of the West, acknowledging the fact that they were now employed under decent wages and conditions.

Facilitator: That's wonderful. And I guess, as well, is there anything finally, Helen, that you really want to share in terms of your story, or if there’s you know a key issue or a key campaign or something really, you know, personal to your story that maybe we haven't kind of covered already? I know that, again, we've talked about a range of different issues. But is there anything that you additionally want to sort of share as part of your journey?

Interviewee: Not really. I think we've covered most of the stuff that I kind of thought you might be interested in. But I guess, as I say, while I'm not working in the union, and haven't been for some years, I'm a very proud life member of the Misso’s, I'm a proud life member of Unions WA. And so am still involved in, you know, a range of different ways. And most of my work these days is perhaps more in the community sector, reflecting those old social work roots than in the union movement, but still, it’s the same issues really.

Facilitator: And have you been able to, I guess, take across some of those insights, or some of those lessons learnt from the union movement to your work now?

Interviewee: Oh, absolutely. And people say to me, things like, Oh, you know, you really, I guess, when you've been used to the union movement and the challenges and the difficulties that we've had there, other meetings are fairly straightforward. Because people's lives are at risk. For 20 years, I had the responsibility, well, I felt right at the responsibility, in terms of thousands of workers and what I did impacted on their wages and conditions and working life.

So, that kind of responsibility and knowing the decisions that you made, and how important they were, I think I take that sense of, you know, what is important into other meetings, the kind of challenges we've talked about, it doesn't faze me. Public speaking, it doesn't faze me going into meetings and, you know, holding my own. It doesn't faze me when people have a go and attack me, and I say that people well, you know, I had 20 years in the union movement. You do develop a thick skin. So, I think those things have all stood me in very, very good stead, some of those experiences.

Facilitator: Wonderful. Well, thank you so much for your time today, Helen. It's been an absolute pleasure, hearing your story and the sort of multifaceted areas that you've been working in. It's been so wonderful to hear. So thank you

Interviewee: Thank you.

END OF TRANSCRIPT