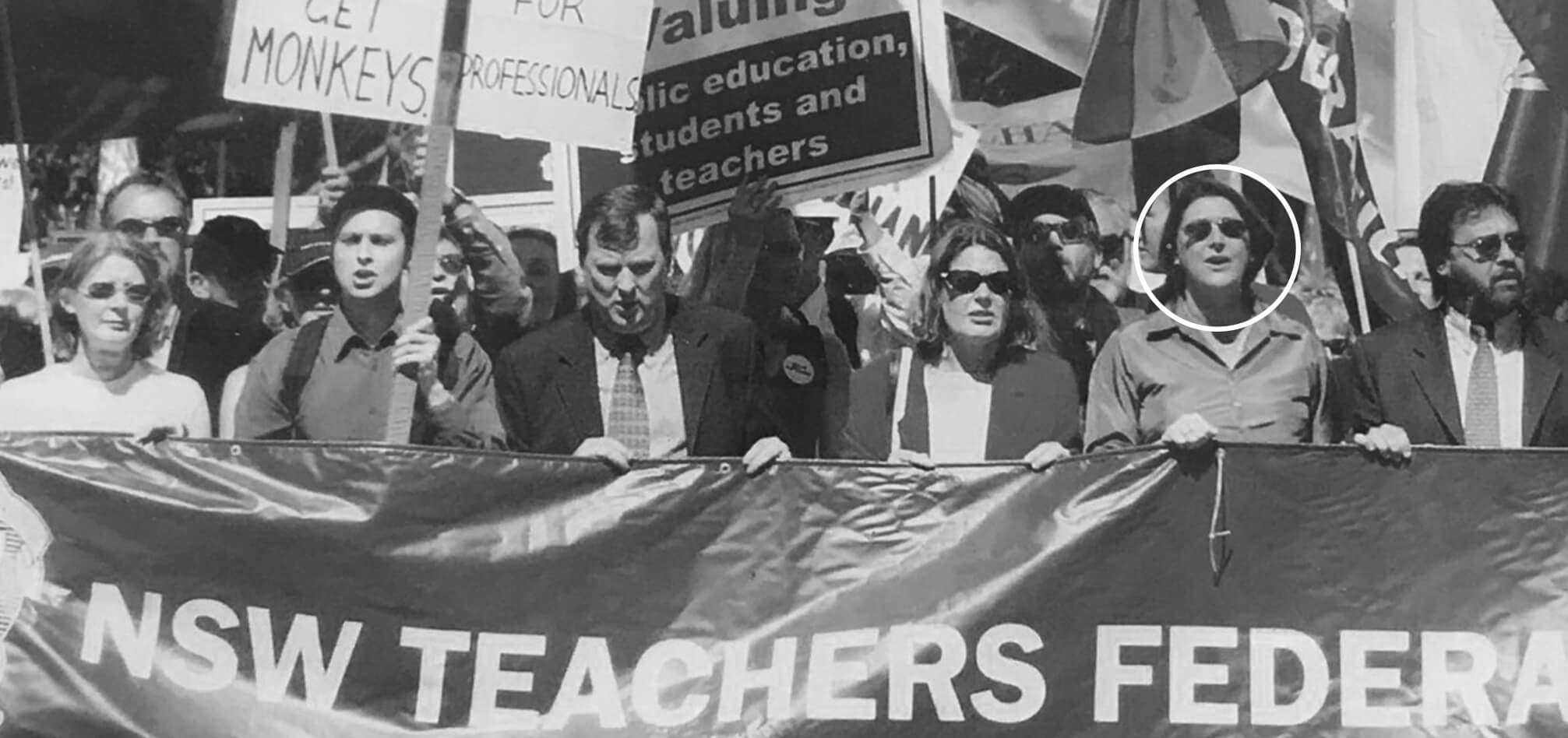

Maree O'Halloran

About this interview

Maree O'Halloran reflects on her time as a teacher, an activist and a member of the NSW Teachers Federation in various roles.

Transcript: Maree O'Halloran Interview

START OF TRANSCRIPT

Facilitator: I suppose the purpose of the interview today is really to capture some of that narrative and that story from your own words and your perspective of what it was actually like working in the New South Wales Teachers Federation and your, your activism that led you to eventually work in the Teachers Federation and hold several different roles during that particular point in time. So, if we can sort of start right back from the early days being a teacher and being an activist as well. Can you sort of explain for me firstly how you actually got involved with the Teachers Federation and when that particular point in time was?

Interviewee: My first appointment as a teacher was at Wade High School in Griffith. I went out on the mail train actually to replace somebody who was on maternity leave. I was engaged immediately at the school by the Federation representative at the school and I joined of course [I was very enthused]. I had the opportunity to attend a council [a Federation state council meeting] not in the first years of teaching. A council of the Teachers Federation is a council of [approximately] 300 rank and file members from across the state and at that time they met 10 times a year to develop the policy of the Teachers Federation and the direction.

And what was amazing to me at council was people taking control of their own work and how they thought that the work should be organised, and the agency that came with that. Then instead of being directed in a hierarchical way of how you should engage, it was about our responsibility as teachers and how we believe the system would be best organised. And that was astonishing to me and I was captured by it and engaged by it; and I was engaged by the debate at council. It was at the start, at the school, where you were engaged by the teachers to become part of the union and part of the other services the union provided at the time, but it was also then the representative model of the Teachers Federation and that so many rank and file members were involved in the direction of the union.

That's my major memory of being just captivated by the debate, by the positions being put, and they were different and they [the strategic and policy positions] had to be - the debate honed the positions to the best possible strategy that we could put forward. That was very important to me and very developmental.

Similarly - well not similarly, but at the same time the Teachers Federation had trade union training and so I took part in the trade union training and again, I found that a very important experience to have the political [trade union and industrial] education that went with the type of work I was doing and to bring the two together.

Facilitator: Did you hold any particular roles at that workplace level; a fed rep role?

Interviewee: Yes, I did, but not in the first year of course.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: I held a number of roles, federation representative, women's contact and then I was a councillor.

Facilitator: And so did you have any family history of activism and being involved in the union movement, or were you sort of one of the first ones.

Interviewee: No, no. It's interesting because I've actually looked back into that because I wondered where did this passion and enthusiasm for the union movement come from [I wondered whether there was a history because of my absolute passion and enthusiasm for the union movement]. And, this I only found out later – that my grandfather, his family was [brothers and sisters and his father were] very strongly involved. They were miners and representatives of that union. And in fact, when he [my great grandfather, Mick O’Halloran] died the whole mine closed and everyone [the whole town] went to his funeral. So, there was a commitment there [to unionism, collectivism and the value of working people]. And looking back into the history of it [the archives about my family] there was a whole debate [that] happened amongst the men because it had been 100 days since they'd had a strike. They thought they'd better have one or otherwise that people would think that they no longer had the capacity [or will] to do so.

Facilitator: That's it.

Interviewee: But look, no. In terms of my actual family of origin, no. Left leaning, Labor [voters] but no activism in terms of the union movement in part because of the nature of the jobs that my parents held. [My partner and my brother have both been workplace union representatives.]

Facilitator: Okay. And so, you’ve mentioned...

Interviewee: So sorry, I should say that I really came to the union movement through study at university and then the lived experience [of working]. And, so, I had a lot of part-time [casual] jobs when I was at [school and] university and I had a lot of experiences that led me to think, well, I'm extremely well qualified as a teacher, as a young person, and I can handle this experience, but what’s…what is happening to the other people in these workplaces.

Facilitator: Okay. And I n terms of working in the Teachers Federation itself, so can you describe for me what elected roles you held within the Federation?

Interviewee: I was elected - well, first of all – I not elected, but it became important. There's a program called the Anna Stewart Program which is a training program for women. At the time it was really by lot so I put my name in the hat and I was pulled out. But that became a very important experience for me because I was then able to understand the connection between the work we were doing in the classroom and the work that was happening in the union.

Following that I was elected as a research officer and then an industrial officer. And then I stood for election for one of the, what we call the presidential officer positions; the ones that are elected from the rank and file, and I lost an election and returned teaching after that [this time in TAFE and Corrective Services]. And then I came back [I stood] as senior vice president [for 2000] and then president [for 2002].

Facilitator: Okay. And in terms of running for the role of president in particular, can you sort of pin point what made you decide to run for the role of being the president of the Teachers Federation?

Interviewee: I can't really. I can’t really. There came a time I think when I thought that my experience as an industrial officer would be useful in the senior officer team and that I didn't see myself in the role of president; I saw myself being part of that team and I stood for the role of deputy president.

Facilitator: Okay. So was there any encouragement from other officers or even from the membership for you to stand to be president?

Interviewee: When I came back to stand as president, certainly there was, there was yes, support from officers of the union and from the councillors. In particular I think I feel the council were supportive. Yes.

Facilitator: Okay. From that perspective, I'm trying to get a bit of a sense of whether you had any key mentors to sort of guide you through your experience working in the Teachers Federation and sort of gave you that encourage to develop your career further within the union?

Interviewee: I think the problem - I have to just go back to the question. You don't really develop a career in the Teachers Federation.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: And so, you don't get mentored to develop a career in the Teachers Federation. [There is of course education and training to develop skills, knowledge and understanding.} You’re rank and file teachers, you come into the union, you give your best for that period of time and then you go out of the union again. [As a rank and file member, you come into the union office from the workplace and you give your best for that period of time that you are elected. So I wouldn’t say that Teachers Federation seeks to develop people for a career as a union official. The Teachers Federation doesn’t develop a career as a unio official. Having said that, I do wish to pay tribute to everyone who has held an officer role in the Teachers Federation. The work is challenging and they are all absolutely committed to the membership.]

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: However there were many people I could name who were supportive [ of me and who helped me at all times].

Facilitator: And there was a particular point in time, I believe when you were senior vice president, if that's correct from memory, where there was three women holding the...

Interviewee: Yes.

Facilitator: ...senior officer positions...

Interviewee: There was.

Facilitator: ...in the Teachers Federation. Can you sort of explain for me what the significance or what the impact of having three strong female leaders in the Teachers Federation at that particular point in time?

Interviewee: Well, it was a significant point in history; it was the first time that we'd had a combination of the presidential officers that were all women. I think it was a very important point in time for the union. We represent teachers, the bulk of whom are women, and so I think that was critically important. I don't think it particularly changed our strategies or of the campaigns that we ran, but it was important in terms of the representative nature of the union and the recognition that there was no problem at all with three women effectively running the union.

Facilitator: Okay. From that perspective as well, in that particular period of time but I suppose more broadly across your time as being president of the Federation, was there sort of sense that being a female leader that there was extra pressure on you to sort of drive, quote, quote “women's issues" for teachers and for members of the Federation?

Interviewee: I think first of all, there'd been women presidents before me, obviously Jenny George and Sue Simpson, and they had forged a way I believe that was very important and I was lucky to have that legacy to draw on. You are driven as a president of the Teachers Federation with such a passion to make beneficial change across the system and for teachers that there are multiple campaigns running at every given point in time. [Campaigns for pay equity, for example, were critically important.]

The bulk of our campaigns, of course, help women collectively [I would say that all of our campaigns of course helped women collectively] because the bulk of the membership are women, but there was obviously a view for, well, are there particular issues for women that we need to bring forward; and there were. For example, in the award, there was a position of assistant principal in the primary schools that was not paid as much as the position as head teacher in secondary schools. And if you look at that the reason would have to be a pay equity reason, that the bulk of the primary school positions were held by women; and we did change that structure. We changed the structure in the primary school and it primarily was beneficial to women. And that was, that's just one example.

Facilitator: Excellent. And you mentioned as well there are a few, a few key female figures in the history of the Teachers Federation who have really held those very senior and strategic positions in the Teachers Federation, and obviously the Teachers Federation has become more feminised over time in terms of the membership base; but still largely skewed towards mostly male leaders within the Federation. Did you sort of see any particular barriers in that sense of there being mostly a legacy of male leadership within the Teachers Federation?

Interviewee: Well, I think you need to look to the reason for that. If you look at the female presidents of the Teachers Federation, I suspect that…well I know that I haven’t got children. So, we didn’t have the parental responsibilities that many of the women in the workforce that we would be drawing from. In that sense, we didn’t have those barriers. And that is one issue that I think we did need to look at in the union. About how those barriers could be broken down. They’re very demanding roles of course, but there must be a way of accommodating them. [Partly that would be an historical issue for all institutions in a patriarchal society. Another huge issue of course is the need for many women to balance their role caring for children with their work life. I wholeheartedly support the union movement’s continued fight for more structural and industrial changes to recognise all the unpaid work done by women in our society.]

Facilitator: That was something I was interested in as well, in asking you with respect to - what is it actually like in terms of the work demands and the work pressures of being a president or being a senior officer working within the union movement; and is there even that capacity or that thought to balance other areas of your life at the same time?

Interviewee: Well, there wasn't for me. I think that could be different for everyone. I also think that we need to look at the roles of presidents in different unions. So, the Teachers Federation model, the president is the senior elected person from the membership and it's a full-time role; that's not necessarily the same in other unions where sometimes they're honorary positions and elected by a collegiate model. So, that's number one.

Number two, you take on the role hoping that you're going to achieve some beneficial outcomes and your whole, or my whole, focus was externally faced about the government [on creating the thesis for the future of public education and the industrial framework for the teaching profession] and the governments changes and the view that the government [successive governments] had failed public education [and TAFE] and teachers and how could we rectify that. How could we take the thesis and put that thesis out there to people about what the system should be like.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: I didn't even think about work life balance. But I point out again I don't have children.

Facilitator: The demands and yeah.

Interviewee: The demands were, so you could get a phone call from - and at the time the media was different; so, far more intense in terms of television, radio and newspaper because we didn't - social media was in its very early forms, if at all I think. Yeah, 2009 maybe it started, and I'd left the role. You could and I would be called at say 5:30, 6:00 in the morning and you might take your last call at 10:00 o'clock at night. The span of hours was very long and the requirement that you be on top of your game at all points because you're representing teachers so you couldn't afford to make a mistake. That’s a very intense pressure because you know the teachers look at you and you represent them so you can't afford to make a mistake no matter how tired you are. That sort of pressure is very intense.

On the other hand, if I compare it to teaching, the actual workload and the intensity of teaching - I've never done a job as hard as teaching. So I could quite easily say the job of being president of the union – qualitatively different of course and a greater span of hours and having to deal with far many [people] and a range of stakeholders – but the intensity of teaching [is tremendous]. I’ve never done anything like that. [It’s often uplifting as well and there is always an amazing sense of hope for the future of your students.]

Facilitator: Okay. From the perspective of being a rank and file female member of the Teachers Federation as well, I'm trying to get a sense of, from your time of being in the Teachers Federation, what sort of support there was for rank and file female activists to be involved if women with children do want to be involved with the Teachers Federation but they are sort of balancing those different teaching commitments and family commitments as well. How much was that sort of recognised by the Teachers Federation sort of having a large demographic of female members?

Interviewee: [Women definitely did want to get involved at all levels of the union. I just wanted to recognise that some women faced more barriers than I did.] It was always a strong focus for the Teachers Federation both in the area of policy development but also in its own structures to the extent that it was possible. For example, childcare to be available for the councillors so if they wanted to be part of that council, which is the critical decision-making body of the Teachers Federation, then there was childcare available for that. A women's officer and women's programs - the Anna Stewart Program I spoke about - trade union training specifically for women. What I would say about that [your question is that there was a focus on] policy development [and] structures in the union itself to try and encourage women to come in and specific women's only courses and training.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: And specific roles in schools called the Women's Contact. I had that role at Griffith High School as a young teacher.

Facilitator: Okay. Those were sort of existing programs within the Federation?

Interviewee: Existing and developed over time.

Facilitator: Okay. Wonderful. Holding that president position for a number of years in the Teachers Federation, how would you describe what your leadership style was in that particular time? Whether that be compared to who came before you or people that, you know, you looked up to in particular. If you had to categorise who you were as a leader, how can you describe what those sort of characteristics would be?

Interviewee: I probably can't describe attributes that I had myself but I can describe the rules I had for myself about how I engaged; maybe that will help.

Facilitator: Yeah.

Interviewee: Okay. So, I had a rule of absolute transparency so that I was transparent at all times with the officers and the members of the Teachers Federation, so there would not be any view that there were closed meetings, closed deals, that anything that happened the members were entitled to know about. I had a rule that I listened to everybody's voices that I could [including all] the officers so that I could get the best possible outcome. And I had a view that you had to be as strong and radical as possible for as long as you could, and then once you started to feel that you were compromising, that you should step down from the role.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: I don't know that that really describes it.

Facilitator: Yeah, so what do you mean by just that last part of …yeah?

Interviewee: Well, the aim is to get betterments. We’re [education was at that time] the largest item on the state budget of New South Wales. Of course, there's the issue of federal funding as well. [However, the State Governments were responsible for the employment role. Of course,] it is incredibly difficult to achieve change that requires funding. So, the aim is to engage with the state government [as employer] by persuasion, by militancy, by whatever avenue and strategy [including better education policies and other gains both industrial and professional] you need to to achieve the policy outcomes and the betterments. And if you feel that you're going to compromise on that or that you can't fight as hard as that; or you're not willing to be out there that strongly and be that visible, then you should step down from that role.

Facilitator: Okay. And the points that you mentioned about having that transparency about why particular decisions were being made...

Interviewee: Or what was said in meetings.

Facilitator: ...or what was said, what actually took place; why was that so important being a leader to have that sort of transparency and for your members to be aware of, you know, this is the direction the union is taking? Or…

Interviewee: Because there are governments at various times, and we see it today, that put in place laws that are designed to constrain unions or make them less powerful or reduce [their relevance to workers] - my view was that the only real way to break a union was to break the meeting of minds between the membership and the leaders - the people who are running the union, but in particular the president. So, I had the view that I needed to continue to ensure that the members knew exactly what we were doing and why; particularly if we're going to take them on very hard pieces of industrial action, like 24 hour strike one week, 24 hour strike the next week. People won't go with you if they don't think there's a purpose, a reason and a full explanation of why. SO it was about the meeting of minds between the leadership and the rank and file members.

Facilitator: Okay. And through your time working as an officer, what were the key, whether it be issues or disputes or campaigns, that really had some significance to you or really characterised your time working with the Federation?

Interviewee: Okay. The Vinson Inquiry [into Public Education in NSW] was obviously an important part of my presidency. It was really about - at the time, 2001/2001 [1999/2000], the state government was restructuring high schools and we were starting to lose the concept of a comprehensive high school where everyone's educated together. And I think I've told you this in previous interviews.

Facilitator: Yes.

Interviewee: But in any event, there was discussion of the executive and the council and we just didn't think there was any purpose any more going to government or going to the Department of Education as supplicants and saying; look, we think this is the wrong direction because it just wasn't changing anyone's view of the world. So that's why we engaged the Vinson Inquiry, we talked to the P and C at the time and they were equal partners in the whole process. We basically said, look we don't believe that the government of the day or successive governments have taken public education in New South Wales in the right direction and we proposed to set up an independent inquiry into the provision of public education in New South Wales.

And what we said to the members is, because we were using members' funds to run what at the time cost I expect about $1 million in the early 2000s; this is the biggest Inquiry since the Wyndham Review, which was into the HSC [it led to the introduction in 1962 of, amongst other things, an extra year of secondary schooling and the HSC. By 2000, we believed that Governments had failed us and teachers and parents had to step up. In many ways the Inquiry was a success] because of the quality [the ability and independence] of Professor Vinson and his team. They visited everywhere in New South Wales [towns, schools and other venues across NSW to take evidence]. They had held public meetings [across the state] that were advertised [along with the Terms of Reference. Submissions were taken and a booklet and the Inquiry’s findings, plan and costings was placed as an insert for the Sunday papers to reach as many households as possible. The full report was published by Federation Press.]

And the report came down and on the basis of that report we were able to achieve a number of changes including smaller class sizes kindergarten to year two. Now, that had been a very longstanding campaign of the union. No one person owns a campaign, but [I would like to acknowledge] Jennifer Leete was the deputy president [at the time] who was pushing [leading] their class sizes campaign [for many years]. The Vincent Inquiry Report gave the [added] impetus and research model [a strong research base] and basis [to allow us] to get that breakthrough. [More funding for teachers’] professional development for teachers, a whole range of [beneficial] changes happened [were won] as a result of that enquiry.

And it also laid the groundwork for our salaries campaigns [and our ongoing] public education fund [funding campaign]. It was an important foundation for the future campaigns in that time.

Facilitator: And what was your role sort of right at the early stages of holding that inquiry into funding in public education? Can you sort of describe how that came about or what your thinking was behind it?

Interviewee: Sure. Yes. I think I was the senior vice president at the time so it must have been either 2000 or 2001; I think 2000. I took a proposition to - we were having a debate at the executive level about how would we engage the government around the restructuring issues. And it was happening at a range of places; Dubbo, Sydney, that the schools were being restructured and the teachers were uncertain about - and the community was uncertain, and the parents were uncertain, about whether these structures were the best way forward. The current president, Murray Mulheron, said [to me]; look, maybe we better have a review because there's no point going to government, why don't we have an academic review. And I said; look, I just think getting at one piece of research is not enough to tip the balance here.

And I had [previously] taught at Corrective Services and I had heard of Professor Tony Vinson as a result of that and he was then at Sydney University [he was a former Commissioner of Corrective Services. By 2000 he was a Professor in the Education and Social Work Department at Sydney University and had published extensively into socio-economic disadvantage.] So, I [simply] wrote a letter to him and I said that we wanted to do this inquiry [into the provision of public education in NSW] and would he be prepared to do it [to be the Inquiry Chair]. And he rang me up and he said yes, if you're really serious about; and that's how it started. So then we engaged - and I said to him; look, we need to have it as an Inquiry across - like a Royal Commission into public education. And he sat down [with me] and we wrote the terms of reference [that day] and off we went.

Facilitator: Wonderful.

Interviewee: It was actually. Amazing.

Facilitator: Were there any other campaigns; you mentioned sort of salaries campaigns as well, or even state election campaigns that might have been important during your time with the Federation.

Interviewee: I should just say that at the end of the day [I started to see that] all the campaigns are really once campaign that’s really a world view around what education and the value of teachers work [one that valued public education, teachers’ work and shared prosperity in society. We sought social justice as well as industrial and economic justice] versus neoliberalism really. [Neoliberalism was in full force by the time I became a senior officer. That is not to say that we did not have significant wins. We did.] But if you want to break them down into parts, there were some significant wins, for example, in the TAFE sector where we achieved an award that meant that part-time casual teachers would be able to get what's called related duties pay. So, in the past you would engage a casual teacher, they were paid only for the face-to-face teaching and not for preparation time. That was - appears to be a small but was a significant win at the time in the face of the ever-increasing casualisation of the TAFE workforce.

The adult migrant education sector. Now, at the time achieving permanency for the teachers in that section, sector work was very important. Those areas of the Teachers Federation that were smaller than schools but still very important in the provision of public education.

The salaries campaigns were always important But the value of teachers' work, unfortunately in the society we live in, value is attributed by how people are paid and the value of teachers' work is much more than their salary and trying to make a significant difference to salaries is a difficult one given, given that we were at the time the biggest item on the state budget.

So salaries campaigns were important because you could engage every member, they [these campaigns] had a momentum and you could, as well as getting a salaries increase, you could also look at other structural changes that needed to happen in the school [or TAFE College]. And with the momentum of the salaries campaign, [you could] add that [issues] to that claim and try and get some sort of structural breakthrough that way.

So that's why the salaries campaigns are important, you would be able to engage every member, you would be able to get a structural breakthrough and you would also recognise the value of teachers' work. And then of course there's the question of public education funding which is a longstanding campaign in the Teachers Federation, but the need to make sure that we have [significant and fair] federal funding as well as state funding.

Facilitator: Okay. I like how you've sort of portrayed the picture of the campaign work of the Teachers Federation being this one world view of public education being against neoliberalism or capitalism or whatever it might be. Could you take that similar sort of philosophy of that sort of the heart of the work of trade unions similarly of having that sort of defensive strategy or resistant strategy against...

Interviewee: Yes.

Facilitator: ...some sort of other force out there?

Interviewee: First I should say it's not just a defensive strategy, it has to be about the future and an optimistic strategy for change. [It has to be about creating the future.] If you take a view that you're going to defend public education or defend public health that’s not going to be [on its own] a successful campaign, so we never took that view in the Teachers Federation. Of course, we would defend; you would defend but you would also put forward an optimistic agenda for change.

In terms of the broader union movement, I suppose I would say this: my view about the one campaign about how we should educate our children and how teachers should be valued, is somewhat predicated on the fact that we were the teachers in the public education system and the public education system has been under attack by neoliberal philosophy. Now that's not to say it's not the same in other areas, but I'd be - I just wouldn't want to say I think that's the case across the whole union movement. Because I think each union - it's important that each union is grounded in its own workforce and its own rank and file members and they all have their own place to play.

When I went to the Welfare Rights Centre I was engaging with many unions because they were supporting and funding the Welfare Rights Centre and every union has its own strength and has its own way of campaigning and they all come together to collectively support workers.

Facilitator: Okay. Looking at your time, whether it be a school teacher activist before coming to the federation officially or that time as an officer, what would you describe or say as being particular barriers or any sort of key challenges that you faced in your union work; whether it be having a particular voice on a particular issue or leading the union in a particular direction? Can you sort of reflect on what were the main sort of challenges that you faced being a leader or leading the direction of the federation in a particular way during your time?

Interviewee: In general or because I was a woman?

Facilitator: I suppose we can say generally, first of all in terms of the union's work and then yourself as a leader as well.

Interviewee: All right. I think the general challenge in the leadership was to ensure that the members were engaged and understood the strategy that you were engaged in and the campaigns; that was fundamental. And the communication with members would range from direct face to face in TAFE colleges and schools where you would visit, the representative council, but most teachers heard us through the media. So at that time most teachers would hear the message through radio, on the TV or in the paper, and while we had the education journal, we didn't have the same opportunity to directly talk to teachers via email or via social media. So that meant that the messages that came through the media were particularly important and recognising that the bulk of the media wouldn't have been supportive of our campaigns, I thought it was important to ensure that I was as clear as possible in the media.

And so, in terms of barriers, I was quite frightened [concerned] about doing the media when I started. I just thought to myself; why don't I just say what I think as a teacher about what's happening; and that's what I did. So I remember we had an award case when we got a plus six per cent pay increase [over two years]. And I was outside the court and I said [to the media conference]; “you know, we just didn't get enough, we have to fight harder, that's just not enough”. And I can remember the lawyers at the time [being surprised] saying “why did you say that wasn’t enough it was more than many people have got” [because they believed the case had been well argued and the outcome was good]. But I [instinctively] knew that thats what the teaches would think [that they would have been disappointed given the industrial action they had taken and the evidence put in the Industrial Relations Commission] and it’s what I thought. So, does that make sense?

Facilitator: Yeah, it does. Definitely.

Interviewee: Okay.

Facilitator: How was that relationship like with the media? I mean, obviously education - public education being such a public facing thing in the community, how did you sort of navigate that landscape?

Interviewee: Okay. I had some advice from previous presidents. And I should preface what I'm saying now, the world is different now.

Facilitator: Definitely.

Interviewee: For example, now you might choose not to engage with the media on some occasions. That might be a good tactic because you can directly talk to your members in other ways. We didn't really have that option, so I took the view that we needed to be the authoritative voice in education and in industrial relations for teachers, which meant that I answered questions on everything. So, I didn’t just say “well I’m only talking about the campaigns that we’re running”. So if the media came to me about an issue that was happening in a school [or TAFE College], I would respond on behalf of the union and on behalf of teachers so that our voice was out there. And of course, that's why the demands were so high.

But I do remember a journalist saying to me very early, if you're available be available to us and then your voice will be out there. And actually, that was true. It was tricky because sometimes you'd just get a call about a subject and you'd have to work out what was either the policy of the union or what should be said about that matter within a couple of seconds. But because you were living and breathing it [the issues] every day and because you'd been a teacher in the classroom, that wasn't as difficult as I thought it would be.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: I remember having to do the 7.30 Report once and being extremely nervous about it and just thinking to myself; well, everything the union's ever done for you has got you to the point that you can do this for them, and get up there and do it. So, yeah…that's how it worked. So, in terms of barriers, I was worried about the media, but as it happened, that over time that did start to work, and we did become that authoritative voice.

Other barriers? The multiplicity of issues in the workplace for teachers and their concern for their students meant that there were so many campaigns that we could be running, and we had to make choices, strategic choices about those campaigns. That wasn't always easy because you could see, you know, in some critical issues that the union just wasn't able to deal with it at a particular point in time. That I'm sure was frustrating to some members, but those choices had to be made.

Facilitator: Okay. And in terms of those sort of competing, the union can't do everything at once, at the same time; how, how was that strategy sort of navigated? Did that mostly come from the leadership determining the strategy or members saying this is what we want to be the priority focus for the union?

Interviewee: Yep. Well first, there would be centrally run campaigns and of course the local associations would also have some local based campaigns and the schools would meet, so there would be some issues that would be run at local level. The remit of the senior officers and the executive were to put plans to council about where we think we should go into the future and then those would be debated at council and changes made and amendments made.

So, it would be developed at the leadership level and debated at the council and then put into place. So, the council, they were representatives from across the state who were elected for that purpose and then they would go back to their local membership and discuss and organise the campaigns. But there was also either - there's an opportunity at council for resolutions from the local areas to come up and some of those would be taken onboard. For example, in the state election of 2003; might be 2002; there was - it came up from the floor of council that we should hold a major event at the town hall and invite politicians to speak and we took that on board and we did it and it was extremely successful. And it wasn't part of the leadership strategy at all; it had come from the rank the file. It was a combination.

There would times, for example, with salaries campaigns you'd start planning for them about 18 months before the award [nominal term] finished. You'd do a survey - or I would do a survey of the membership and then on the basis of what came back, look at what the claim should be going forward and then go to council and get them decide whether or not that was right. So, there's a combination of strategies. But essentially, the leadership is there, we can't have a vacuum, so the view is that you put, you put the plans to the members and then let them debate them.

Facilitator: And I think your time as being president was quite unique as well in the political landscape for the fact that there were so many education ministers and director generals...

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: ...through that particular period of time. And can you explain what, what that experience was like given public education is so politically driven as well; how you sort of navigated that landscape?

Interviewee: Yeah. I can't remember the exact turnover now, but I think it might have been six ministers and five directors general in the time I was the president for seven years. So it meant that you never had one contact that you could speak to in government [even though there were some Ministers that I respected]. I have to say though that I would never have been a person who’d want to engage in or form a relationship with – even a respectful mutual relationship. I wasn’t a person to pick up the phone to government. So, I would be more likely to ask people to go on the streets and then pick up the phone to government. [In hindsight, I wish I had tried to establish better relationships to benefit the members. I always wanted the union to speak form a position of power and not as supplicants.]

But it did actually help in some ways because the turnover of directors general and government ministers, each one had to get across the brief every time they came in. It meant that they were a little off the mark, I think, and not able to get on top of the issues as quickly as perhaps they ought to have. So I t gave the union some more power, in my view. In a sense, when I look back on it, it was almost like they vacated the field or it was too hot to handle.

Facilitator: Okay. So do you think that your campaigning might have been strengthened in that sense because, you know, everyone in the department or the government was a bit scattered at that stage?

Interviewee: No, I don't think it made a difference to our campaigning, I think it made a difference to whose voice and whose ideas were heard publicly. The union develops ideas [tested with the membership] in its private membership and then our job as the leaders is to take that [those ideas] externally and win the debate. And it meant that our voice was heard more clearly publicly.

Facilitator: Okay. Reflecting on, your career with the Teachers Federation and the activism that you had during that particular point in time; reflecting on that, what would you say that you're most proud of? Or what has been some of the most enduring memories that you've since taken away from that period of time?

Interviewee: Sorry, I was hesitating on that.

Facilitator: Yeah. Yeah, no.

Interviewee: Look, I think - I remember when I stepped down from being the president and I was really proud that I had successfully represented teachers for the seven years, if that makes sense. What I was most proud of is I don't think I deviated from good faith with the members and I, I certainly was proud of that. I was exhausted at the end of the seven years; and I'm sure everybody who's had the role is, ‘cause it takes every fibre of your being to be able to do it. But at the end of it I was just, I was extremely pleased that I was able to do it to the utmost of my ability.

Facilitator: And I know that now that you're in a different line of work, you're not working for the Teachers Federation any longer; I suppose it's a bit of a two part question. But, what made you decide to step away from the Teachers Federation, and how have you since used some of those learnings from your time with the federation?

Interviewee: So I was at a council - no I wasn't it, I was at a [the Teachers Federation] conference in 2008 and the conference is 600 members who come together once a year; and I just remember standing and I had to give a speech and at the end of the speech I just had this visceral reaction that my time was finished. Only ever had that sort of feeling twice in my life. Once was when I knew a relationship had ended and I had to end it; and this was the second one. It just - it really came from nowhere, it wasn't like there was pressure that I should go, but on the other hand, I still - we all hold the view in the Teachers Federation that you do a certain amount of time and then you let the next person take - you don't, you don’t sit in positions for years and years and years.

So, that happened and then the question was in my mind; well, do I go back teaching? I'm a good teacher; I'm a very good teacher. I'd been out of the classroom a very long time. There would have been an enormous amount of work for me to do to re-establish myself as a teacher, but that wasn't really what stopped me going back teaching.

But I also had had so many clashes, particularly with the principals secondary principals, council. I just wasn’t sure how comfortable principals were going to be with me being a classroom teacher back in their school. [I’d had a high profile and had been confrontational having led a lot of industrial action and industrial campaigns. That might have been difficult back in a school – hard to say.] So, there was that as well. [Instead, I took a position as the head of the Welfare Rights Centre.] So, I went to the Welfare Rights Centre – because I also have a legal degree – it's a community legal centre that is in part funded by the union movement and in part funded by government to help people on social security payments; people who are unemployed, people with disabilities.

And I thought that was important because one of the things about the union movement is it's really an important movement for workers, but it also recognises that there are workers who are jobless and they're jobless because we live in a capitalist society so there's a structural rate of unemployment that’s going to be there at any given point in time. And that's established so people will be disciplined into taking low paid jobs. And there are people who are jobless because, for example, they have a disability, or they have other [significant barriers], so to me I saw it as an extension of my role in the union movement.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: Yep.

Facilitator: I know that we've spoken a little bit about barriers and challenges that you sort of experience within the Teachers Federation; but reflecting more broadly on the trade union movement and unionism overall, right from the beginning, before you worked in the federation and then comparing that to when you then left the Teachers Federation; can you sort of see some change with respect to the barriers or the challenges that you saw for the union movement overall from that beginning stage to then when you left your career as well?

Interviewee: I think that - well first of I'll say that I think I was fortunate in the time that I was a union leader and I'm also fortunate that I was a union leader in a craft-based, professional-based union that has a very high density. For me the union movement is critically important to workers. We are seeing that the union movement is – there’s a lack of members or a loss of members [there’s a need to rebuild a critical mass of members]. And I don't think it's because of the message we have, I think it's because of the nature of work and the changing nature of work and it's just simply not as easy to organise in the gig economy. But I do, I do think that union leaders like Sally McManus and others, are - clearly, they recognise this and they are working around that model [and to focus on job security].

I've also seen unions like the AMWU, for example, they have an office space. I think I might have talked to you about this before; but they have an office space and they - if you're a union member but you work in technology or IT and you work as an independent contractor or you're doing - they have office space where you can go and work. So that’s recognising the new nature of work and how we work around it.

I think that one of the things that I did see clearly as I came into the Teachers Federation is that we were dividing work into those who would have autonomous jobs and those who would be highly directed in hierarchical work. And I think that we see that happening, that division between highly paid workers who work autonomously and those who are under minute supervision and then those who are in the - even worse situation perhaps – in the gig economy.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: I think that division is happening more clearly.

Facilitator: And In that sense, I mean, the Teachers Federation being a public sector union or professional union in that respect, representing professional workers; are they facing the same sort of challenges from your perspective compared to unions who are now having to represent workers in a more fragmented sense? What do you sort of see as the federation's biggest challenge at the moment? From that sort of outside perspective.

Interviewee: Yeah. No, I hear your view about the public sector versus the private sector and I that that in part is correct. Although all of the public sector unions now are dealing with a 2.5 per cent legislated wages cap, which is actually damaging the economy as a whole and even the RBA governor, while he hasn't said it recently, has said that the 2.5… the government wages caps do affect the economy generally.

So, dealing with government where they have legislated powers is in itself quite a difficult prospect, while I accept that dealing with a private company is equally difficult in its own way. In terms of organising, the Teachers Federation has experience in the TAFE area of the destruction of the TAFE system and the difficulties and recognising that we see that happening in some of the private sector as well.

Facilitator: Just finally, Maree, reflecting on your time being a member of the Teachers Federation – having an officer role as well; is there anything that sort of reflecting, sort of sums up your experience over that period of time and anything we haven't discussed yet, which you think is really significant to your narrative being an activist?

Interviewee: I think the absolute commitment of the Teachers Federation to the collective wellbeing of its members and their students, is just something to be utterly admired. And I t's not something that you - while I'm no longer an elected official of the Teachers Federation, it's not something that you ever walk away from, once you've become part of that. For example, going to the council as a young person, it wasn't just the question of agency over your own work, it was also a political forum. So, it was where your political voice – so it was a public [it wasn’t a party] political forum. It was a political forum where publicly you could voice issues to be raised and then debate them. [Most importantly, your voice was equal to all others. You were not constrained in the forum by your place in the world or the constraints of an employment contract. You were free.] So, yeah, that's what I'd say about the Teachers Federation.

I think that there's no doubt in every generation of the federation [that democracy is fundamental]. Sometimes very difficult because there's so many democratic decision-making processes [in the Federation], but worth it, at the end of the day.

Facilitator: Okay. Excellent. Was there anything else from today's conversation that you wanted to add or a final reflection?

Interviewee: No, thank you.

Facilitator: That's it?

Interviewee: Thank you.

Facilitator: Okay. Wonderful. Thank you very much.

Interviewee: Thank you.

END OF TRANSCRIPT