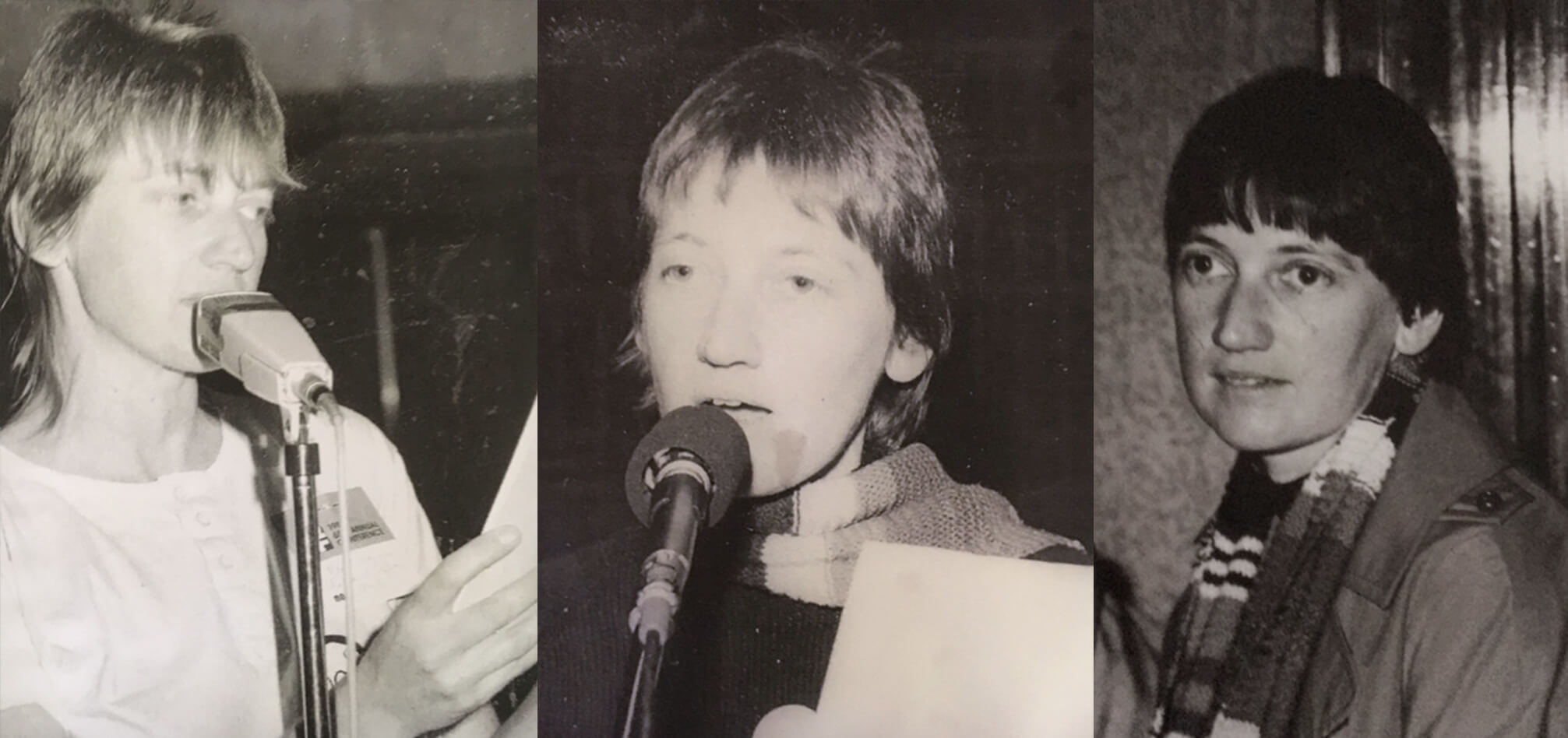

Anne Junor

About this interview

Anne Junor speaks about her time as a union activist, driven by her own sense of social justice. As an educator and member of both the NSW Teachers' Federation and the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU), she fought for gender pay equity – among other issues.

Transcript: Anne Junor Interview

START OF TRANSCRIPT

Facilitator: Thank you so much Anne for joining me today to talk about your experience being a union activist and being a union officer and your experience in two unions: the NSW Teachers’ Federation as well as the NTEU, the National Tertiary Education Union.

Today’s interview is really about trying to capture your story and your experience of being an activist in your respective unions and thinking about your lived experience being an activist and a unionist during your time.

I thought we could start right at the beginning and talk about how you first became involved in the NSW Teachers’ Federation, first of all, and what sort of time period is that that we’re talking about.

Interviewee: Okay, well we’re talking the mid-1960s, which is just before feminism really took off in Australia, but the early…well the 1960s. Interesting enough, and I had no concept of this at the time, we did have equal pay in New South Wales because that came in for teachers in 1958, and so it was never an issue. But, of course, I began in 1965, which was 3 years before the first national equal pay case. And, so, we are talking about a long time ago. I became a teacher when I dropped out of higher degree study because I got married, and I married a Vietnamese at the time when there were only a thousand Vietnamese in Australia and racism was really still rampant.

And, so, I guess I had a sort of a sense of social justice and it just…I can’t remember how I became the Federation Representative at my first school. But I think it was probably by default because I was the most vocal on social justice issues. And for the rest of my time as a teacher, and briefly as a Teachers’ College Lecturer in Armidale for a couple of years, until I became an elected union official. So, from 1965 through to 1982, I think I was always the Federation Representative in whatever school I was in. And…where should we go from there?

Facilitator: What sort of area were you working in, in terms of the geography that you were working as a teacher?

Interviewee: Okay. Well, I was probably fairly lucky in that I was an English and History teacher and I worked at Willoughby Girls High, I worked at Maroubra Junction Girls High when it was still in existence, and in my fourth year of teaching I happened to be the most senior person on the English staff, and I was appointed the acting Head Teacher of English and History. And that was in the years of the first teacher strike, that was in 1968. And, so, it was interesting that both the principal and the maths head teacher, as well as myself, were supportive of the strike. And in fact I was interviewed by the Herald out at Wentworth Park, and complaining about workload, even in those days.

Facilitator: Still talking about it today.

Interviewee: Yeah, yes. So…what can we say. When I finally became a real Head Teacher in the late 1970s, I knew very little about formal union structures. And we had really terrible physical working conditions viz none of the windows would open. And not knowing anything about protocol, I actually organised a strike, supported by about 80 parents. And we all just marched into the city, turned up at Federation House. Jennie George was the General Secretary, and we said ‘here we are, we’re on strike’. And to her credit, wonderfully, Jennie George sort of swallowed deeply and then said ‘oh, okay, well we’ll organise this’, and she…they obviously got on the phone and we went on a deputation to State Parliament House. That wouldn’t happen these days. And we got our windows, we got our opening windows. So, there you go.

At the end of that period, during those years I joined an activist group within the Federation. I was elected to Federation Council, and so learned how to conduct myself in the very strenuous debates that happened once a month at Federation Council of about 300 people who came from all over the state as Councillors in what was a very democratic union.

We were part of a bit of a ginger group that was somewhat activist. And we also supported the emerging organisation of women arguing for, not only pay equity, but other issues that affected women teachers. In particular, promotion was an issue at the time. There were still separate male and female promotions lists when I started, and Barbara Murphy was one of the people who worked on that. But there were a number of us.

And the other one that was just emerging as an issue was sex-based harassment. And we experienced…ah, that’s a bit later, when I was in the Federation itself. The union itself was not immune from harassment. What can I say? So, to support each other…Oh and the other thing that I was particularly interested in was curriculum issues, and particularly as an English teacher for students from non-English speaking backgrounds. And I became an elected union representative on the senior English syllabus committee and was one of the people who put forward a proposal for a special English course for international students and students from non-English speaking backgrounds.

Now…I’m talking now about the period 1978 to ’82 when I was still a school teacher, Head Teacher, and a Councillor, and an activist. And this was a time when women started to, I guess, organise mutual support groups so that we could be more effective in debating at Council because it was not easy to debate in Teachers’ Federation Council. For a start you had to get ‘the call’. And you could be virtually standing on your chair and waving your arms around and miraculously the Chair mightn’t notice you. So, it was even quite hard to get the call. And it was scary actually to stand out in the aisle and speak when you might have been speaking against, or trying to change, or shift along, official union policy.

So, out of all of that, we formed a mutual support group advocating, if you like, more, ah, we would’ve thought more progressive policies that shifted agendas along. For example, on the very unpopular issue of sex-based harassment. And, also, HIV/AIDS was starting to emerge as an issue and we were starting to formulate union policies on HIV/AIDS. Frank Barnes was also a member of our little group of Leftovers.

And the Leftovers were very supportive of women’s autonomous mutual support groups. And out of an election of Federation officers in 1983 I became a Research Officer and Darelle Duncan was elected as Women’s Officer, following Gail [Shelston] and a couple of other Women’s Officers who came out of the 1975 International Women’s Year. So, what am I trying to say here….? That Darelle’s approach…actually Darelle and I, and a number of other people, stood against each other as Women’s Officers, and I was so glad that Darelle got elected and I didn’t because it turned out her policies were much more progressive than mine would’ve been, in that she was very much into grassroots women’s organising.

And this was seen in the period 1983 to 1988, this was seen as divisive and separatist. The women’s action committees that were really Darelle’s signature policy were started in those years and there was a lot of opposition to them. And my little Left dissident group, who we used to meet before Federation Council to work out how we would put forward progressive amendments and so on and support each other. And I mean it was really scary to take part in the debates. And we were very tough on each other too. I remember my very first Leftovers meeting that I attended I said something nervously and timidly and somebody said to me ‘don’t be so bloody ridiculous’. And that was the sort of way we treated each other in a way, it was a tough school. And it had to be. Anyway, so that’s that.

During the 1980s when I was a Federation officer, there was of course the Accord and the….virtual impossibility at ACTU Congress, so anywhere else, of raising of policies that might be disruptive of course to the Accord. And the nurses equal pay case was run in 1985, and again, that was framed in a way that wouldn’t have any pay increase for women, wouldn’t have any economic impact. And so therefore by definition it was not going to bring about equal pay.

So, people like Jennie George who were, I think, quite sympathetic, but they had to be…I mean we were unrealistic. We didn’t realise the need for gradualism. And so we were, if you like, a bit too bolshy and militant, and Jennie was playing it step by step and getting there in the end. Yes.

Facilitator: And if I can take you back Anne as well. So you mentioned you first were sort of driven by union activism because of this investment or interest you had in social justice issues. Would you say that was the main thing that really drove your activism? Did you have any, you know, family history of union activism or anything else?

Interviewee: Oh, absolutely the reverse. No, no, no. No. No family history whatsoever. I would’ve thought that my parents would’ve voted Liberal, hmm.

Facilitator: And you spoke also about how one of your first roles in being activist was a Federation Representative at the school level, and then you were elected as Research Officer?

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: In the Teachers’ Federation. What motivated you to, sort of, take that next step to kind of move into an actual officer role within the Teachers’ Federation?

Interviewee: Policy debates…Ah, at the time there was a very strenuous debate about working class kids’ education and whether subjects like maths were of interest to working class kids. And I was one of a group who was very much against any streaming of kids.

And I mean the debate, looking back on it, was over simplistic, and these days I would be more supportive of alternative curriculum for kids who weren’t very interested in the academic stream. But in those days, it was a way of streaming out, there were no qualifications attached, like there was no vocational stream in schools. It would’ve been a matter of streaming kids out forever from any further opportunity. And I had this sort of idealistic view that education is liberating. That whole…it’s almost disappeared these days with everything’s vocational, isn’t it? But just the idea of a broad general education for working class kids.

And so that was what the debate was about. And it was my absolute passion and adherence to non-streaming that led me into the Research Officer’s role in the Federation. From there I became active at the national level because state-based research officers all provided support to the national union’s research agenda, and I was particularly interested in Indigenous education and women, so they were my two portfolios.

Facilitator: And you’ve given me a very comprehensive overview, Anne, of the range of issues and range of campaigns that you’ve been involved in at your time being a Research Officer with the Teachers’ Federation. Is there something that sort of stands out from your time as being most memorable or something that you’re particularly proud of from your time as a Research Officer or you felt you really make a strong impact during your time?

Interviewee: Yes, actually. Privatisation. Ok So that was the other…there were two further strings to my bow, if you like, as a Research Officer. One was that the Leftovers group that I was part of, many of them were also members of the Defence of Government Schools group. But we were passionate supporters of public education. I remember in 1983 when there was a debate about private school funding. Private schools were divided into like Catholic, systemic, so-called ‘poor schools’, and independent schools. And the debate ran, if you like, the ALP supporters within the Federation would’ve supported this line, that there’s a commonality of interest between poor Catholic diocesan schools (systemic schools), and public schools, and that it’s only the rich private schools that should not get funding.

And I argued very much against that, and I argued that that’s all very well, but if you look at the way the Catholic system is run, they actually, even back then, they stick together, the diocesan and non-diocesan, and they distribute funds among themselves. And you can’t do that, that would just open the flood gates to private school funding.

And, of course, that has just proved so true. And the other thing I’m proud of was that I developed a policy approach to new private schools. And, so, we used Dubbo as a test case, and we argued that to open up a small Christian school in Dubbo would in fact take away the range of electives from not only that school, but the two other public high schools in the town. And that you would end up with less curriculum overall, and that proved to be true. So, I developed a new schools funding policy that the government should fund new private schools only if there was no adverse overall impact. And Susan Ryan supported that, and there was…in those days there was a New Schools Policy. But, of course, it fell over. Yeah, so there was that. And the other thing I’m proud of is that very early on, I supported the TAFE Teachers’ Association in their struggle against casualisation. And that, that emerged into my PhD, that case study became one of my PhD case studies, and then that flowed through to my work in the NTEU on casualisation.

Facilitator: Anne, you talked about your time being part of an activist group, an activist faction, within the Teachers’ Federation. Can you tell me more about that experience and what it was like being part of that particular group?

Interviewee: Well, obviously the group itself met before every Council and Annual Conference meeting to thrash out the pros and cons of every policy proposal. So it was like really intensive workshopping, and working out a position, working out arguments…it was really just like brainstorming and intensive thrashing out of policy issues.

Early on that group supported multicultural education which was also always in danger of falling off the agenda in the Federation because, you know, the idea you’ve got to stick to the big picture, the mainstream, you can’t deal with these little side issues like women, or etc. And so…I guess we were prepared to be deeply unpopular and provided support to each other. This is sort of my rosy view.

We would be seen by other people as disruptive. I think we made a lot of mistakes, but we were young…we weren’t young, but we were rash, we were…We took accountability very seriously, you know, pore over the financial statements and everything…We took all of that: ‘This is existing policy, the policy is the bible, you can’t do that because it’s against a policy that was made X years’….you know, a bit self-righteous.

Facilitator: And can you tell me more, Anne, about the nature of Council debate within the Teachers’ Federation and what that experience was like for you?

Interviewee: It was heated. It was far too inward-looking actually, far too inward-looking. And people firmed up their positions. But I guess out of it came…Let’s say everybody took policy very seriously, and also took holding the officers, the elected officers, to account very seriously.

Now the Leftovers, most of us, held very, very strongly to the view that a union official is a representative, an elected official, and that you mustn’t seek election for more than two terms because if you did, then you’d lose your appointment in a school, and that you had to go back to the grassroots and not be a lifetime officer. Now that’s fallen by the board. But we really believed that strongly in those days. And that we had to go back to our Association’s and account and report back. So, you know, we would’ve, self-righteously, taken the idea of democracy very seriously. So, yeah, that’s what it was like.

Facilitator: You mentioned your time being involved in very progressive issues for women and women teachers in particular, and even within the union space itself, did you mention that you were one of the forerunners in designing the Women’s Action Committees, and being part of the Action Program?

Interviewee: I didn’t initiate that. Darelle Duncan really was the person who did the research and the thinking on that, but I was very supportive. So, there was a group of us who were very supportive of all of it. But I guess because I was a slight, always had a slight research…well I was a Research Officer. I don’t really know why, but I was approached by a group of women from across a number of unions, and also because the 1980s were the ‘golden age’ of women’s units in government departments that really arose out of International Women’s Year, the 1975, and flourished in the 1980s and, of course, Labor was in government nationally, so there were many directorates, women’s directorates, at both state and federal level.

And the women who…I guess a thing that I haven’t mentioned was the political parties involved, and obviously Left women in general, like particularly I would think, although nobody talked about it at the time, but I would think a number of them would have come out of the Communist Party, and other…well what was left over from Women’s Liberation and women’s collectives.

And, so, in 1988 there was a socialist feminist conference, big socialist feminist conference, and out of that came the National Pay Equity Coalition. And I was approached to join that group and learnt so much from those women, those wonderful women. And gradually we met, during…from 1988 through really till 2000….really till 2012, although for some of those years I was in Canberra, really developing strategies for advancing pay equity. And out of that gradually came the pay equity inquiry in NSW in the 1990s.

Now that happened at a time when I was very involved in elder care and not able to go to meetings, and then from 1995 to 2000 I had my first university job and that was in Canberra. But during those years, the National Pay Equity Coalition was instrumental with the help of Jeff Shaw in NSW in setting up the pay equity inquiry, and Philippa Hall, the amazing and wonderful Philippa Hall, was head of the women’s directorate in NSW, or maybe deputy head I’m not sure. Meredith Burgmann who’d been active in the forerunner of the NTEU, and then the NTEU by 1992, and other women. And so they met at Meredith’s place once a month, and again, bit like the women’s action groups in the Federation, just thrashed out policy approaches.

And out of that came the formulation of the, gradually, the historical undervaluation approach. Because of the setbacks to pay equity, really through the Accord, through the disaster that was enterprise bargaining, and NPEC remained very vocal, and very unpopular in the 1990s. Like agitating at ACTU Congress etc, arguing that enterprise bargaining was bad for women. That put Jennie George in a real spot, because being inside the ACTU and working from within by then, she had to go along with the enterprise bargaining line in the 1990s.

And, so, because enterprise…decentralised bargaining was spectacularly making it harder to achieve pay equity because the legislation had changed, and from 1993…I’m sorry if I’m rambling a bit, but the 1993 Industrial Relations Review Act cross-referenced the industrial relations regulation system with the anti-discrimination system. And that seemed to be a good thing at the time, but how it panned out in equal pay cases like the HPM case in the 1990s was that employers were able to set it up so that you had to prove the intent to discriminate as a threshold requirement before you could run an equal pay case. And so equal pay cases fell over.

And the requirement to find a male comparator was just like hopeless because of the…job segregation, because of the emergence of service work…because this is something we forget, that during this period, service, if you think about it, clerical work was totally changing with computers, and that was one of the early things that NPEC was on about too, and its forerunners, about what office technology meant for women, and women’s skills. So, we were very interested in the idea of identifying women’s skills.

And then care work became like the, if you like, as more women came into the labour market, care work became monetised. And so, I mean we forget, but these were sort of new and growing occupations at the time, and NPEC was struggling to formulate conceptualisations of the valuing of women’s skills and women’s work, and the NSW pay equity inquiry, Meg Smith was one of the really pivotal people in this. So, they were looking at the value of women’s work in and of itself because there was no comparator.

And out of that came the National Pay Equity Inquiry of 1998/99, came the first equal remuneration principle of 2000 in NSW, which established that you didn’t need a comparator and that women’s work had historically been undervalued and there were indicators of undervaluation, such as casualisation, low unionisation etc. So the indicia that were in the 2000 principle developed and improved on in Queensland, and then applied in the SACS case in 2010-12. So, like, NPEC was just like, really if you like, the thinking behind all that.

Facilitator: And I know that you also worked with the NTEU, which I want to get to shortly, but I just want to ask you to kind of reflect on again your time at the Teachers’ Federation and if you had to sort of say what was the main challenge or the main barrier that you faced in your union work….what would that have been? Can you pin point one thing, or a range of things, that were a real struggle for you to, you know, get the union’s attention on an issue. Can you sort of reflect in that respect?

Interviewee: Ah yeah, it’s the dilemma that everybody faces working inside and outside the system. It’s the dilemma of what is actually achievable. And how far you push the boundaries for what you know is the ideal thing. So, you’ve gotta move things forward, but these days, looking back, I wouldn’t have got so upset about things that weren’t achieved. I would’ve been much more philosophical. Like our favourite word was ‘sell out!’, you know ‘sell out!’. And, of course, that people like paid officials, in a union, are going to have to compromise. It’s exactly the same thing that’s happening in the NTEU at the moment of those, I think, you know, very distressing purists who were critical of the NTEU’s current struggles against what’s happening in the sector. But a union has to compromise. A union has to do what’s politically achievable. And we didn’t understand that. And so we were always saying ‘sell out’.

But on the other hand, I do have to say that the people affiliated with the ALP within the Teachers’ Federation caved in too easily, and they had too many other ties and they weren’t prepared to push hard enough. So, if you like, we were the self-righteous little ginger group pushing too hard, and not being very kind in the process, being very dramatic and tragic about it all. But, yeah, and I mean…it’s like watching The Good Fight every week, you’ve gotta understand I guess the working, it’s the absolute dilemma of feminists, of working inside and outside the system.

Facilitator: And, so, you stepped away from your work with the Teachers’ Federation and being a Research Officer. Can you tell me what motivated that decision, and where your journey….?

Interviewee: Oh well, I, I was determined that I wasn’t going to outstay. I was a strict adherent to the ‘union officers should be of the rank-and-file and not, and shouldn’t be lifelong sinecure’. But also, by that stage, I really did want to do academic work and also my aged parents needed care. And, so, I started a PhD at Macquarie. As one of my case studies, I used the TAFE anti-casualisation campaign. And there was another case study, I looked at one of the first call centres in Qantas, and the third one was banks, frontline officers in banks.

So that took forever, and then I got an academic job, and then I became an academic. But both Meredith Burgmann and Caroline Allport took me under their wing a bit at Macquarie University when I was a casual. But from the very beginning, I mean, the NTEU was formed 2 years before, was it 2 or 3, 1992, 3, I became…I got my first continuing academic job, and that was fixed-term, but then it converted, in 1995.

And then by 2000 I’d, I was a Councillor, National Councillor, and this is a sign of how brash I was I guess, I already talked to the union about [seeking] funding, going in with a SPIRT grant, a Linkage grant, to look at casualisation. Graham [McCulloch] wasn’t that keen [to outlay money initially], but Chris Holley from NSW was extremely supportive and I worked closely with Chris, very closely with Chris. And I went back to the Teachers’ Federation as an Industry Partner and also for the TAFE and schools part of the study of casualisation. So, yeah, that was my first academic research was on education industry casualisation. Yeah. And the other string, the two other strings, always public sector work and….like my PhD was on skill and flexibility, and so I was– always the casualisation was one part of it, and the skills of women’s work was always the other part. And so the gender and skill.

Facilitator: So, with the NTEU as well, so you’re a member of the NTEU?

Interviewee: I’m proud to say I’m a Life Member.

Facilitator: Life member. And what then inspired you to be involved with the work of the NTEU, stepping on from your work of the Teachers’ Federation?

Interviewee: Well, it was just a continuation that…I was a Councillor from very early on. So I went to National Council meetings…

Facilitator: Is this a Councillor with the NTEU?

Interviewee: NTEU. From the time when I got my first academic job in Canberra. Even when I was a casual at Macquarie I was doing research funded by the Department of Industrial Relations Pay Equity people, that’s where I did the bank case study. It was just like the gender thing, and the casualisation thing. It just became issues that needed to be taken up. I dunno really…There were fights, I was at the University of Canberra, there were fights about conversion of fixed-term contract people that I was involved in. I was just like naturally on the enterprise bargaining team. I dunno, I just…always on a Branch committee, so it just seemed what you did.

Facilitator: Are there particular defining moments when you were a National Councillor for the NTEU that stood out as being particularly significant during your time?

Interviewee: Grahame wouldn’t remember this, but I stormed out of a…when I didn’t get my way about something on casualisation, I stormed out of a National Council meeting. But Grahame came and we sorted it out, and, and that was alright…Anything else….no I was not particularly prominent or anything, I was just, just there.

Actually, an important issue for me. But by this time I’d shifted to UNSW in 2000 and again I was on the Branch Committee and again I went to National Council, I always went to National Council. I was on the [UNSW] enterprise bargaining teams with Sarah Gregson and others. They were pretty torrid, the enterprise bargaining at UNSW was just like, oh…it was terrible actually. The management were very uncouth, put it that way. And I very much admired our organiser Jeannie Wells, and but you could bargain for more than a year and it seemed to get nowhere. So, there was that.

I was never particularly involved with individual cases, on the Cases Committee, I’ve only just become involved in case work. And I have great admiration for the patience of people who do individual case work. My latest involvement has been heartbreaking because it has been trying, unsuccessfully, to support the early childhood… ‘early years’, they call them, early years workers in the four early childhood centres at UNSW, all of which are being closed down and outsourced, or being outsourced under much worse conditions. So, one of them is being closed, the other three are being outsourced.

So, yeah…I would have to say that I’ve been fairly marginal. I’ve just been a Branch Committee member and a Councillor. I was very interested, however, in the debate of 2012 over whether to sacrifice the long-held doctrine that academic work involves both teaching and research. And to support the idea of conversion for casuals into what was obviously likely to be teaching intensive roles. And I was one of the people who supported that. I supported the Scholarly Teaching Fellow model and it’s been very ambiguous. It has created tenure for 800 people, of the 55,000 casuals in the system, and so, yeah, I was lucky enough to contribute to a research project run from UTS by James Goodman and Keiko Yasukawa evaluating the STF initiative.

So, no, I’ve been a pretty marginal…I mean active enough to be a Life Member, but marginal…I have to say I was never considered as a Life Member in the Teachers’ Federation because I was of the dissident faction. Although I do think I did make a contribution on the privatisation issue. The other thing I did in the Teachers’ Federation, I was the Research Officer appointed to the Lecturer’s Association before the formation of the NTEU. And they made me a Life Member.

And I wrote many-a submission to the, as it was then, the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission. Not always gratefully [received by the national body of the Australian Teachers Federation]…there was a bit of a demark between NSW and the AEU, or its predecessor the ATF, the Australian Teachers’ Federation, about whether a mere state-based Research Officer should be dabbling in these issues. But, yeah, the Lecturer’s Association organised college lecturers, rather than university. So, except at UNSW where the casuals who weren’t getting much support from FAUSA, the predecessor, the university predecessor [of the NTEU], and the casuals joined the Teachers’ Federation.

Facilitator: Anne, you’ve talked about a whole range of very progressive issues you’ve been involved in in terms of pay equity for women and cases like that, and my question is going to kind of reflecting on your entirety of being a union activist. Did you experience any sort of struggles or any sort of opposition in being very progressive on issues like pay equity for women and trying to really improve the pay and conditions for women workers and women teachers in particular?

Interviewee: Did I encounter any…?

Facilitator: Were there any barriers, any opposition, from perhaps within the union, or like to the issue in particular? Or was everyone like ‘yeah this is a….this is a…we’re on the same page with this’, or…?

Interviewee: I reckon they were debates about strategy.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: Not about objectives. And, also, of (a) strategy and (b) priority. Like do we have time for these marginal issues? How marginal or how central is multicultural education? For example. How marginal or how central are casuals? How much of a side track is…well, one in particular because it did divide men and women, really, because there were male unionists who were the offenders, was sex-based harassment. That was always a very fraught issue, particularly in the 1980s. And was it a legitimate union issue?

If I could say that perhaps there were better strategists than I was. And people like Frank Barnes who was able to make HIV/AIDS an issue that everybody went along with, from very early on, that’s seen as a union matter, and getting a unified progressive position on it. And Australia was really, in those days, a leader in approaches to HIV/AIDS. So, I think Frank’s more inclusive strategy, he was a Leftover, but he had a more inclusive manner.

And so, yeah, I mean we were all for the biff and the fight and the debate, you know. And in fact we ran a journal, a little…it only ever a couple of issues came out, maybe even only one, called ‘Open Debate’, as the implication being that debate on Council wasn’t open, it was constrained.

Then the other thing where there was a real difference of opinion was what’s best for working class kids and migrant kids, do they…as they were called then, migrant kids. The issue of special treatment versus inclusion. And it was a debate that was also run in relation to special education. And it’s a tricky debate. In a funny way, even though I fought Laurie Carmichael tooth and nail about gender issues, that Carmichael model of pathways from vocational etc, from you know, formal qualifications that provided pathways, that would’ve provided an answer, not streaming…well, see, that was the debate, it would’ve ended up in streaming in schools anyway. So, again, it was that debate of what’s achievable, and how do you get equity…the perennial same versus different debate. So how do you secure inclusion without marginalisation? How do you specialise without marginalisation. And it’s a resource question.

Facilitator: And thinking about the work of unions overall and the purpose of unions, how does the work of unions today, compared to your time, what would you say are some of the main challenges that you faced as an officer for the Teacher’s Federation, compared to what…today?

Interviewee: Look in those days, all teachers, virtually, were union members. And we had the luxury of being able to conduct policy debates about philosophical issues, like social justice issues and so on. I mean these days we’re saving jobs, we are defending pay, and we’re defending conditions. Conditions have just deteriorated so much, and job security.

I mean, even if you think about it in a global context, in most countries of the world, people in the formal labour market are about 10% of workers. I mean most workers aren’t even employed. I mean there’s…what was I reading this morning about, oh, it’s an NTEU issue of that music teacher employed by a private so-called university as an independent contractor, not even as a casual, not even the dignity of an hourly… the fiction of an hourly paid casual actually employed for a session, but as an independent contractor. So even the status as an employee.

And the other thing that’s just gone by the board is any employer commitment to, I mean as a Marxist I would say, as the reproduction of labour i.e. enough time to rest, enough sick leave, retirement income. Employers seem to have even backed away from what’s in their own interests of maintaining an ongoing supply of labour. So like the deterioration since the 80’s, 70’s, 80’s and 90’s has just been so stark.

Facilitator: And this is I suppose one of my final question Anne, and very welcome if you want to contribute other comments as well, but if you had to sort of reflect overall your entire time, very long experience being a union activist for multiple unions. Is there anything that you can sort of step back and say that was a really defining time in my life, or my career, or that’s something particularly that I’m really proud about? Is there anything you can sort of pinpoint in that respect?

Interviewee: Well you see that’s individualises it, cause I was part of a movement, it wasn’t me. And so participation in the mobilisation of women, within the union, was important. I had no idea at the time of the significance of the work of NPEC, but looking back now, I see that it was groundbreaking. So, I had no sense of it. I don’t think any of us did at the time, because we were finding our way, we were nutting through issues. Yeah, but overall, I mean overshadowing everything, is the casualisation, the loss, the loss of an employment relationship and the loss of regulation of the employment relationship.

Facilitator: And is there anything else you wanted to add today Anne? I know we’ve covered a lot of territory and a lot of wonderful insights from your time, but anything you wanted to contribute on the record?

Interviewee: No. I mean has that of been of use?

Facilitator: Absolutely, absolutely, sort of capturing your life story being a very active union member, so, no, that was wonderful.

Interviewee: Okay. Thank you very much.

Facilitator: Thank you so much Anne.

Interviewee: Well, thank you for the opportunity to look back and reflect.

END OF TRANSCRIPT