Chris Wagland

About this interview

Chris Wagland recalls her history of union activism and her belief in the power of people’s stories.

Transcript: Chris Wagland interview.

Facilitator: You've just told me when you started and how you joined.

Interviewee: Yep. So I joined when James was six weeks old and became a union member on my first night there. I've been a member ever since. I worked part-time. Not very involved with the union other than being a member until probably - we had a really dodgy contractor, which is usually how most people end up - start getting involved in the union, it's because there's been a disaster. So we had a contractor in 1995, and when they finished in 1998 we didn't - that's when I became a union delegate. We'd had them in and out of court for a number of - the union had had them in and out of court a number of times over underpayments. When they finished the contract they owed - they refused to pay long service leave and other entitlements.

So I sort of helped Lyndal, Lyndal Ryan, the union secretary, so that was sort of - and basically there was a lot of older cleaners who were being bullied. Basically they stood behind me and pushed me out the front, and said Chris, you do it. A lot of them didn't have English. So I was just petrified standing there, and they were like look, we've got your back. But…

Facilitator: So what did that entail, that first…

Interviewee: More just speaking on their behalf. It was just a boss who was a bully, and then because I became the delegate, tried to change my hours, knew that I worked mornings, but I started after I dropped my boys at school. So then of course first thing he said we're in breach of contract. You're to go back to starting at 6am, even though I'd been given permission to start at half past 8, knowing full well that I couldn't start at 6. Of course I was dreadfully upset. I went - refused to change his mind, carried on, and then I spoke to everybody - I did a lot of - it's a bit hard to describe. The rooms I did, the areas I cleaned, were for - they were locked at night time. So they were only done during the day. So I did…

Facilitator: They were still Defence…

Interviewee: In Defence, but within - so there's layers of security within Defence. So I went and spoke to all of them and told them that I didn't know how much longer I can stay. They all wrote me references, including the air vice marshal, because I walked into his office and burst into tears. He was very kind, and whatever you want. His assistant, who happened to be a captain, wrote this most glorious referee report, and said if there was going to be any change to the cleaning, and if I was going to be moved, they would like to speak to someone. So then I passed half a dozen letters on to the manager, and he disappeared into the woodwork because I'd called his bluff and stood up to him.

Facilitator: Okay, so your hours weren't changed?

Interviewee: No. He backed right away, and - so that was - because of that - that was my first - but it's scary, and it's horrifying, and you don't sleep.

Facilitator: Yeah.

Interviewee: The knees shake, and you think oh my goodness, what am I going to do if I lose my job? Of course you survive it and come out the other side. So we won our court case in the Federal Court and got paid what we were owed.

Facilitator: With the same company?

Interviewee: Yes. It took two years.

Facilitator: Right.

Interviewee: So that was all great. Because of that, Wayne Berry, who was a Labor member here in the ACT, put up a private member's bill that gave us portability of long service leave. I sat on the Long Service Leave Board for a number of years, which was absolutely wonderful. It was really nice to help people ensure that they got their long service leave and it was portable.

Facilitator: What was the role of the board?

Interviewee: Just to - basically there was - so we were taken in by the - the construction industry has had portable long service leave, and so they very kindly lent us money to start. So the board was set up as - a chair, and then a member from contractors, and a member from the union, and seconds. So I was Lyndal's second, and originally only supposed to go in case she couldn't go. But then it was sort of decided then you wouldn't know what was going on. So it was just a little board, and we just - it was about getting companies registered, and overseeing how the board worked. That was all very interesting. It was good fun.

Facilitator: Okay, so that's one role that you took on because of your union activity, which was I guess a bit outside of your day-to-day work. So you had your day-to-day delegate's job, and your job at the workplace, and then you had the Long Service Leave Board. What other activities did you undertake?

Interviewee: It's been - then I suppose things have been - it sort of goes in waves. We - 2006 the contract changed hands again, and we were taken over by Serco Sodexo, and it was AWA or no job. I ended up becoming very outspoken again, and refused to sign an AWA. I went with the outgoing contractor. I'd worked at Defence my whole working life, especially at Russell, so I ended up going with the outgoing contractor. There'd been - there was a lot of interviews, a lot of demonstrating, a lot of noise, a lot of talking to people. We managed - because not only was it an AWA, but it was a 15 per cent pay cut. They're just vile people.

It's an award, what are you worried about, it's an award? But it wasn't award, it was the award from Victoria or somewhere. We managed - we embarrassed them, we embarrassed Defence, so we managed to get them to agree to pay the award rate, but not to remove the AWA. We hope that they would eventually - we tried to get them to - that we would sign the AWA if they would agree then to discuss an enterprise bargaining agreement, but they had no intention of doing that. So we managed to get the cleaners award rates.

Facilitator: Can you just give in a bit more detail - because I know for you it's part of the whole campaign, but I think it's really interesting for us to hear about. You said we did some protesting and we did some this and we did some that. Can you explain a bit more of the detail of what that was?

Interviewee: Okay. The thing that worked the most was we left petitions on everybody's desk within - because most people just didn't understand what was involved with the cleaning and how we'd been hung out to dry. So that was - yeah. It was just mainly telling people, educating people. Having the thousand and one conversations. You'd have people stop you in the corridor, or I'd put out the petitions and then we'd collect them, but Defence got very embarrassed by them and wanted all the petitions removed.

Facilitator: So you put petitions and Defence workers signed them?

Interviewee: Mm.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: Yes. To support the cleaners, and to support the cleaners that they should be paid award rates, and that cleaners didn't have to sign AWAs. Then from all that sort of - it morphed into Clean Start, which was about raising the profile of cleaners, and I sort of became a default spokesman on that because of the trouble with Serco Sodexo. So that was - yeah. It ended up…

Facilitator: So that was bigger than just the ACT?

Interviewee: No, yeah, so then it was - yeah. So this is wrong, this is a huge problem that's happening everywhere, we need a big solution. Clean Start was it.

Facilitator: Can you explain Clean Start a bit?

Interviewee: Clean Start is about setting a standard, a minimum standard that recognises and values cleaners and what they do. But also it recognises and values contractors. So the problem there's been is that every time a contract changes hands, they take the cheapest price. Buildings don't shrink. They haven't got any smaller. But cleaners have to do more and more, and then of course you become spread thinner and thinner, and then it's - they have these terms like just do a spot vac. Well if the floor's dirty, how do you do a spot vac? It's just - the words - they've got no idea of square metreage rates or what's involved in cleaning a building.

So it was about making - and it's because we worked after hours, and nobody who - people would come in the morning and find their bins emptied and the toilets cleaned, and the pixies did it overnight. So it was mainly educating people. This is what we do. Because we do a shitty job doesn't mean we should be paid shitty wages. If - and we did. We're just cleaners. So it was very much about not only raising our profile but raising our opinion of what we did, and how it had changed over the years.

When I first started you just cleaned everything every night. Then of course it got to the point that you had to judge every day what was - well I've got to do these basic things. Well then what's the next most important thing I need to do. What comes first? Do I do this - and the constant trade-off. You chased your tail. You never caught up. You never got in front. You just kept it at a level that was acceptable. It's just offensive that you can't - don't have time to do your job properly. You want to, but you just - you do a spot clean and - anyone can do a tidy up around their house, but at some point you've got to clean it properly, you know?

Facilitator: Yeah.

Interviewee: So of course it was - so that was - and the idea was the raise the - and cleaners to have proper training, to be able to have - to have the strength to say my vacuum cleaner's not safe and I'm not going to use it, because I know - because you couldn't get hold of - you'd have a dodgy cord, and you knew there wouldn't be another cord on site, and you still had half an hour of vacuuming to go before the end of your shift. If you went looking for a cord you'd never find one, and of course technically you should have stopped working, I can't do my job, it's not safe. But you didn't.

You'd nurse along a cord that was shorting out all the time in the hope that you could get your work done, and hope you could get a cord the next day, instead of stamping your foot and saying no, you don't supply a cord, I can't do my job, so it's not safe and I'm not using it. Most people are too frightened.

So Clean Start was not only educating cleaners, but educating the client, but also understanding too that I'm entitled to be paid a decent wage, but so is my employer. Contractors - the problem is that the contractors accept a price which they knew they couldn't do the job for, and then bully their clients into doing - until they hurt themselves. That's the other problem. You've got to make people strong enough and confident enough that they will say this is wrong, I'm working too hard, I can't do it, I need more time.

We also wanted - cleaning jobs used to be a good, reliable job with decent money, but over the years the value went out of the job. So part of the Clean Start thing was that the wages would be part - and we ended up that the wages were part of the contract. So you had contractors who were all on the same pay, who are like for like, and you want contractors who do the right thing by their workers.

Facilitator: Yep.

Interviewee: They're not going to go bust and not pay their workers. Then your workers are going to stay. They're looked after. It's a win-win situation. It's very much - if you don't look after people then they're not going to be safe and they're not going to stay, and they'll go elsewhere. Then of course you've got to retrain cleaners. It's in a contractor's best interests to look after their cleaners. The ones that do and did weren't winning the work because they were being undercut. So if everybody's bidding at the same pay rate, that was the idea of Clean Start.

Facilitator: You take wages out of the competition.

Interviewee: Yes, you take it - and then it evens the - yes. Then it's the employer's reputation that wins work, and his reliability, and his accountability. Making cleaning contracts transparent and accountable, all those lovely words that we fought for many words to have put in. So we had the Commonwealth contracts, and we had two vicious years where the - they had agreed to use only Clean Start contractors, but every time it went out to tender they would give it to a non-Clean Start contractor because he was cheaper. So we had this most ridiculous thing.

We had Clean Start contractors bidding at the higher rate, and then of course the bottom feeders, the crooks, all of a sudden they've raised their rate and they're bidding at the award rate. So they're winning work on the award rate, and so the good guys were missing out. It was just - yeah. It was a public service thing that - the public service - they wouldn't - how did they put it? It was about - they couldn't not take the cheaper contract, because that's how contracts had always been let.

It took two years, but it ended up that we got - that you didn't have to be a Clean Start contractor to bid for work, but you had to follow the Clean Start thing. So either you were signed up to a Clean Start agreement, which was basically an enterprise bargaining agreement, and the union - and you had made an agreement with the union. But if you weren't a Clean Start contractor, you still had to follow the Clean Start things about showing that your bills were all up to date, you'd paid your super, that you provided training. So you had to tick all the same boxes.

Then we were able to - while the Commonwealth couldn't say that contractors had to pay the Clean Start rate, the Commonwealth could put in their contracts a preferred rate, which was the Clean Start rate. But that took two years to get in place. Then we only had two years, and then the Libs got back in, and then that vile senator from Tasmania, we became part of the red tape that was…

Facilitator: [Unclear].

Interviewee: Yeah. Clean Start went out the window. Tony Abbott stood in a question - no, you're telling lies, no cleaner will lose money. Well as every contractor's changed it's gone from the Clean Start rate back to the award rate.

Facilitator: Okay. Yes. The Clean Start story. What was your role - what - so you got a role in terms of the union's Clean Start campaign. What did that mean in terms of you and other cleaners? What did you do with other cleaners with regards to the Clean Start?

Interviewee: It's just more - once they know and they see you in the paper then they come up, I saw you, and then of course it's everywhere where I cleaned. I saw you on the news last night, Chris, you know. Then of course any time anyone appeared on TV you were supposed to bring in a slab. That was one of the buildings I've cleaned down at Fairfield. The guys used to say where's our beer? So no, it's just more once they know that you're involved then people will come and ask you questions, what's happening, what's going on? It's more - yeah.

Facilitator: Yep. So your profile then prompts them.

Interviewee: Yeah, and then people hand on my phone number to other people, and I get calls from cleaners at other sites who don't want to call the union, but who want a bit of advice, can someone - and usually it's - I'll pass on that information to Sonia at the union office and she'll do a site visit. Is someone having a problem? This is what it's about. I pass on the phone numbers and do it that way.

Facilitator: In terms of formal union activity, were you on the branch…

Interviewee: Yeah, so I'm on - I became Vice-President of the ACT Branch in 2002, I think. So I sit on the branch executive. Then I attend national conference. It used to be once a year. Now it's every second year, which is always good fun. It's nice to - because United Voice covers such a wide range of industries, it's just lovely to go and all get together. It's nice - we don't see each other from year to year, but to see what they're doing and what's working and what's not, and the different industries and the different states. It's always nice.

So you're feeling bad about something that's not working, but then someone else has had success, so we enjoy each other's wins, but we also commiserate with each other's losses, and where we're stuck, and where the problems are.

Facilitator: Talking about that, you said you're Vice-President, you're on the branch exec, so what type of time commitment - well for all of your union work, not just that.

Interviewee: I suppose it goes in - in the scheme of things I suppose it's not that much. It's - and I couldn't give you a - but other than - branch executive is every four to six weeks we have a meeting which is an hour, an hour and a half. Then other than that it's whatever's happening at the branch, and if Lyndal calls me and asks me to do something or get involved.

Facilitator: So I could imagine though that during some of the campaigns…

Interviewee: It gets busy.

Facilitator: …it gets busy.

Interviewee: Yeah, so there'll be a few things to do, and then - yeah.

Facilitator: And did that - did you feel that that - how did you manage that, given family commitments and actual work?

Interviewee: I've sort of been lucky. My employers have always been fairly sympathetic, and because I've always worked on sites where I was the only cleaner, it's been - I'd work around things. I'd just let them know I'll be off-site for a couple of hours, and more often than not they were good about it. Then I take time off to go to national council and - yeah.

Facilitator: After that initial kind of issue with your contractor that you then sorted out, you got your underpayments repaid, they tried to change your hours but they didn't succeed, was that then the contractor that you left with when Serco Sodexo…

Interviewee: No, there'd been another contractor in between. That was the problem with the long service leave. You had to work - we never left the site, we just got re-employed by the next contractor. So we were on site but we lost long service leave every time the contract changed. We lost our - we got paid out our annual leave, but we lost any accumulated sick leave. That's been - that's part of the Clean Start thing too. We'd have to go back and start again. They'd put us on probation. You were treated that you were - until they - so instead of recognising this person has been employed on this site for 10, 15, years, so surely they must know what they're doing, to recognise that you have been around for a while.

It was more that sort of - new contractors used to like to throw their weight around a bit, just to - and frighten people to see who - instead of treating people with a bit of decency. You've been doing this for a while. If there's any problems with your - because every contractor's got different ways of doing things, but surely recognise that the person who's been on site and has done the work might actually know what they're doing, and say that won't work because of this. They're the contractors you know that say right, well you've been on the site, how does it work, what do we need to do? We'll discuss it with you. So some are good. Some aren't.

Facilitator: Okay, but overall, apart from those initial ones, you've managed to negotiate a reasonable acceptance of your union work.

Interviewee: Yeah. I think the thing that - people tell me I can't be in a union, but I've long since found out contractors will treat someone who's in the union differently to what they'll treat someone who's not.

Facilitator: In what way?

Interviewee: Well because your level of understanding, they - you know what you're talking about, and if you don't you'll go and find out and ask the question. That's usually enough that they think twice before - which I think a lot of people don't realise that - who don't - I don't need to be in the union, but there are - yeah. It's interesting, the number of contractors who will treat people according to whether or not they are in the union.

Facilitator: Okay. That is really interesting. A question that I'd like to ask is - because you were a member for quite some time before you - let's say volunteered to be a delegate. Did you have any family history for unionism?

Interviewee: No.

Facilitator: Anything in your background?

Interviewee: No. It's funny, my husband - I was only 18 when I met my husband, and he was a very strong Labor supporter. I suppose I came from a background of - my father had a small business in Albury, and had been part of the Labor split with Catholic and DLP. So I grew up in a Liberal household and never took much notice of politics, and probably not for a long time. But over the years my husband and I have basically changed places. He became more conservative as he got older, and I moved the other way.

My father used to call me a pinko. That was his - not quite a red.

Facilitator: But getting there. Shades of.

Interviewee: Yes, which I used to always find amusing, which is quite funny because he was always interested, my dad, in what I'd been doing, and he'd have a laugh if he spotted me on the news. What are you up to? I suppose that's part - that social conscience I suppose - I don't know. Being raised a Catholic, I don't know if it - but it gets to a point where…

Facilitator: But no formal union activity.

Interviewee: No, and then just Lyndal volunteering me. So that was - I don't know. I often - I hate speaking. I get dreadfully nervous. I'm no better if I've written the speech or if I have to do it off the cuff.

Facilitator: I think I heard you at the Cleaning Accountability Framework launch.

Interviewee: Yes.

Facilitator: You were excellent. There were no nerves in sight.

Interviewee: They were all in - there's a little voice inside screaming.

Facilitator: I understand that one.

Interviewee: I think - people say we don't talk well, my English isn't good, so I always - and for a long time the union spoke for us, were our voice, and we didn't need to speak for ourselves. But the minute Lyndal stands up to speak or anyone else, there's always that she's got ulterior motives. She's only in it for the money. They don't care about you. Really? But it's that - they like to undermine and white ant, but I tell people I don't care if your English isn't good. The choice of listening to you or a politician, what, they're going to call you a liar and not the politician? I mean they're going to believe the politician over a cleaner who stands up and says I'm not being paid?

That's the power that people don't realise that they have, that no matter how much your voice wavers, or you get upset, or your knees shake, people want to hear your story, not a politician's.

Facilitator: Just a little diversion here, the makeup of the cleaning workforce is, and has always been, quite ethnically diverse.

Interviewee: Yes. I'm a rarity.

Facilitator: Okay. You haven't seen a change? That's been constant?

Interviewee: No, and it's - our biggest was - when I started it was Yugoslav, so Croatian, Serbian, Macedonian, and then over the years it's more Asian content. Now it's Sudanese, Bhutanese, yeah. Lots of - most of the ones that I started cleaning with are all retiring. But the thing is too, when I started I was one of the younger ones, but I'm still one of the younger ones. Cleaning jobs are not career jobs. It lost that. A lot of people who clean will only do it while they're students and until their English is good enough and they can go on and do something else. It's becoming harder and harder. That's part of the fight we have. Unless you make cleaning jobs good jobs, people are not going to want to do them and keep doing them. We're becoming an ageing workforce.

Facilitator: Yep. Were you involved in other community or social groups or other networks as well?

Interviewee: No, not really. Mainly just the union. It's been the only thing I think I've ever been involved with, other than sporting clubs through the boys. No, not really.

Facilitator: Okay. In terms of - you've already given me a taste of the types of activities you've been involved in, but what do you think are the most - so far, the most enduring moments or enduring memories for you?

Interviewee: I spoke to the Property Council. That was rather - and that went well. That was a bit scary. I think when I spoke with my favourite - I love Julia Gillard, so when the Commonwealth agreed to only use Clean Start contractors, and they flew me to Sydney and said Chris, say a few words, with about two minutes' notice, and I thought oh my goodness, so that was lovely. I think - they're all lovely when they're over. I think - there's been some horrific ones. Not really horrific. I think the ones where I get - I've been a couple of times - I think that was when Mark was getting sick, and I didn't realise I was a bit fragile, I spoke - I was at Parliament House and the - we were speaking about cleaners' wages, especially the cleaners at Parliament House.

I was standing with Brendon O'Connor, and I did the spiel, and the Commonwealth - the Parliament House cleaners were standing behind me. I did the speech that I've done, and I could feel myself getting tired and congested. Then I've gone - and I won't say it, but I swore, and I said I'm going to cry. I burst into tears, and I was so mortified and horrified.

[Phone call interruption]

Facilitator: So I'm just trying to remember where we were up to. Your most enduring memories.

Interviewee: Yeah, so I made a - burst into tears, continued, managed to get it out, and told them to delete the expletive, and was horrified. There's five banks of cameras, and just - anyway, I reduced most of the cleaners behind me to tears as well. Then while I was mortified, I kept saying what passion. Nada from National Office, Chris, they keep saying how wonderful you were. I said Nada it was awful. I didn't get half the things out I was going to say. I just got so upset. No, that's all right, they loved it.

Facilitator: It was powerful.

Interviewee: Yes. No, she was so passionate about what she was talking about. She meant what she said. I just felt stupid.

Facilitator: [Unclear] had impact.

Interviewee: Yes. No. I think the first - the first one I've got - actually I've got his picture - is - I told him we lived in the kitchen. He laughed. That was the launch of the Clean Start.

Facilitator: Ah ha.

Interviewee: With Kim Beazley, he was leader of the opposition at the time. We went and met him and had coffee with him. He sent us a signed picture.

Facilitator: Fantastic.

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: Can I take a copy on my phone before I go?

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: That's fantastic. Great.

Interviewee: It's probably getting a bit dusty. He was funny. I saw him, and then I saw him within 12 months. He said you're like the salt and pepper. I thought he's picking on my hair. No, but he meant you're always at the table. So that was…

Facilitator: I like that one. I've not heard that.

Interviewee: No, I hadn't either. So of course I was thinking oh, are my grey hairs showing?

Facilitator: That would have been my response too.

Interviewee: But yes, no, lovely man. Very fond of Mr Beazley. Met Julia a few times. Very fond of Julia. Met Bill too. I didn't think I'd like him, but I do. I think when they're not being minded, and they just get to talk, yeah. That's when you get to know them.

Facilitator: Yeah. So they're the enduring memories. What would you identify as your greatest achievement?

Interviewee: I would have thought Clean Start, but then we lost it, and I think Lyndal and I have shed far too many tears over it. But then it's morphed into the Cleaning Accountability Framework, which I think will - Clean Start on steroids, will be long-term, will be - will survive longer, I think. We dragged cleaning contractors kicking and screaming, but this is sort of a more holistic approach. It's got all the wonderful things of Clean Start, with checks and balances. Because it's in the private sector, I think there's more chance it will come back towards - the governments will recognise it. It's contracting for dummies basically. That's hopefully - yes.

But portability of long service is…

Facilitator: It's a big one.

Interviewee: It's a biggie. Yeah.

Facilitator: What do you think were your biggest barriers or biggest hurdles?

Interviewee: I think the biggest barrier's always going to be frightened people. It's always going to get people to take that first leap into the unknown, to put their hands up that I'm not scared to join the union, I'm not scared to speak up, you can't bully me. I think that's something that we still struggle with. The wins we've had, it's been with little support. Our original fights, a lot of the cleaners - at Defence, a lot of the cleaners were public servants. They were told that if they were caught demonstrating out the front of the building as a cleaner, they were in strife. So there's always - and I think that's - yeah. It's that fear that people are scared to stand up.

I think it's just the way that unions are treated now, that unless - it has to be from the rank and file. We can't just leave it in - no matter how well Lyndal speaks, it's always tainted with the fact that she's in the union, and it's that - that things have to be people-led. It's to get people involved, and that's where it becomes - it becomes harder and harder to - yeah.

Facilitator: So one of the questions I was going to ask was what do you see was the biggest challenge facing unions and your union when you first got involved, and contrasting that with now?

Interviewee: I think given the fights we had, there was more respect for the union then than there is now.

Facilitator: From whom?

Interviewee: Just from - originally the union sat in every time the contract was changed, so if there was to be - because the labour levels were fixed. So if the labour levels were to drop because a building - the union agreed to it. So basically there was an inspection done, and the square metreage rates stayed the same, or if there was an extra building how many more cleaners would be needed, or if one had dropped off how many fewer cleaners, so that nobody lost their job, or if numbers had to be cut that it was done by natural attrition, that people just weren't replaced. It was always - it was very friendly and amicable.

I don't - we were a member of the union, but we very rarely had to call on them. It was just that there was respect and - I think there was on both sides, but then once - it's that awful thing, money. Once you talked about - with the Clean Start - so once fixed labour levels went out the window, the value of contracts went into free fall. So then of course that's been - and that's been the big fight ever since, is to - trying to stop jobs going down the slippery slope. It just becomes how far can they stretch it, which is just ridiculous. Then every so often someone has an epiphany and says oh my God, we just want a clean building, and we'll pay to have a clean building. Yeah.

So you just want - yeah, to be that understanding. People who work in - public servants should have a clean workspace. They should be clean. I always - I think I - in the Cleaning Accountability Framework speech I made, I talked about - we'd clean the building and we'd finish early on Friday and order pizza. But it was not because we were having pizza, I remember it because it was the last time the building was clean. Everything was done. I've never worked in a building since that - by Friday night there's still things that will carry over into next week that you haven't had time to do, or that are not as important, so that you - yeah.

I don't think people understand that - the sense of achievement that you've - when I started cleaning, David was two and a half, a newborn, and I'd leave the house. My husband would walk in the door, and I'd leave to go to work. I'd go into work with a thumping headache and tired and exhausted, and clean for a few hours, and leave headache gone, and you've worked off your stress. That sense of achievement. It's dirty, I made it clean.

Facilitator: You can see what you've done.

Interviewee: That's right. You can see where you've been.

Facilitator: Yep. Okay. You see the big changes being an understanding of the job, but also the status of the union to other parties, to…

Interviewee: Yeah, I mean - and it's - I suppose where it's different now, the idea is to put - I mean the union is constantly spending a fortune chasing underpayments. Let's just fix the problem, and that's what Clean Start is about, and that's what the Cleaning Accountability Framework is. Let's fix the problem, make the jobs better, make it that everybody's getting paid, nobody's being cheated, nobody's getting hurt. That's - in this day and age, I think - I suppose after 30 years of being in the union I want back what we had when I first started, that sort of stability. People shouldn't have to be stressed. They should have time to do their job. What they do should be valued. They should be paid for what they do. I mean that's - people aren't greedy. No one expects to be paid a fortune as a cleaner, but nobody wants to be cheated.

Facilitator: Yep. Just going back a second - well, a few minutes ago you were talking about when you were having your first dispute, and people were scared because they were told that they - if they were public servants they couldn't be seen demonstrating. What is it that's different about you?

Interviewee: Okay.

Facilitator: Because you took on - whether you were being encouraged, you still took on the role of a leader.

Interviewee: I think I got angry. That was - I knew I could not work any harder. I knew I could not do any more than what I was doing, and if they were going to move the fence posts again, then the quality and how I could do my work would suffer, and that - yeah. I just got pissed. Enough is enough. I think my husband a number of times, why are you doing this? Trying to explain - and of course I think one of my sons said Mum, it's just a cleaning job. Why are you fighting so hard? I said because it's my cleaning job. It's my shitty little cleaning job, and I'm not letting anybody else tell me how to do my job. They're my buildings, and they're my - it's my family. I just got angry.

Then of course I remember thinking if I couldn't get another job I'd have to go back and beg Serco - that was my biggest nightmare, and I think I - that I'd have to go back and ask, please give me a job back because I can't find a job. That was my biggest fear. There were months I didn't sleep, or barely slept. I thought oh my goodness, we're going to lose the house. I mean all the things - but I mean it's just - yeah. But you just think - and I had English as a first language. All the others didn't. They're all frightened. The AWA was complicated, and they wanted resumes. They wanted - it was just the most ridiculous things. People would go to interviews for jobs they've done for years. I'm thinking, I'm petrified, what about someone else who doesn't have English?

Then it was just if I don't, who will? That just became my mantra in my head every time my husband said look, you've done enough, back off. It was just no, I can't. I just couldn't.

Facilitator: So you stepped into a leadership role because you felt that there was no one who would do it.

Interviewee: Yeah, I suppose that was - yeah. I didn't think I had any more skills than anybody else, but I just - I don't know. I just got stubborn and cranky, and no matter how petrified or frightened I was, no, I couldn't take a backwards step.

Facilitator: Did you see yourself - do you see yourself, did you see yourself as a leader?

Interviewee: No. I don't. I sort of squirm when you say that. I just - no, it doesn’t. No. It was the fight, and I got involved, but I wasn't the only one. There were others.

Facilitator: When you say there were others, that was one of the questions I wanted to ask. Obviously you're quite close with Lyndal.

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: Was there a group of women doing the same thing in other contexts, or was there a few of you?

Interviewee: Yeah, there was a few, and I think Lyndal would ring and ask them, and they'd just - she just knew I wouldn't say no. No matter how much the little voice said tell her no, she just knew - I mean that was the - yeah. If I have a hero it would be Lyndal. She's just incredible. I've said it lots of times. Every time I think I'd say no, I'd think she works so hard, I have to help. She's done it well. She's guilted me into it.

Facilitator: [Unclear].

Interviewee: Into lots of things.

Facilitator: There were a few, but it was more your relationship with Lyndal…

Interviewee: Yeah. It was just - yeah.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: Then because I - I don't know, I think I - yeah.

Facilitator: What do you see the future holding for your union and for unions generally?

Interviewee: I don't think I like to think that far ahead. I mean I think it's - membership's our biggest problem. I think that's the - anyone who's got a - we're losing members from people who are retiring, and they're just not being replaced, because the people coming in at the other end, who are starting, are like I'm only going to be here for a few years. I'm only cleaning part-time because I'm studying. This is not going to be my permanent job. I don't need the union. That's the biggest thing you have to fight. They just take for granted everything they've got. Yeah.

That's my son coming home.

Facilitator: All right, well that's pretty much it to be honest, just whether there was anything else that you…

Interviewee: That I could think of?

Facilitator: ...that you could think of, or that was interesting and I haven't asked about it, or any aspects?

Interviewee: No, I don't think so. That doesn't mean I won't think of something…

Facilitator: No, and if you do, text.

Interviewee: Yeah. No. I think - no, nothing out of the…

Facilitator: Here's a question for you. Would you do it again?

Interviewee: Yes.

Facilitator: There wasn't much hesitation there.

Interviewee: No. I'd probably still worry myself sick, and grow grey hairs, and embarrass my family. I think - my boys cringe every time, and my husband did too, every time my picture's in the paper or on TV. I just didn't tell them. What they didn't know wouldn't hurt them.

Facilitator: Okay. So you would do it all again.

Interviewee: Yes. In a heartbeat.

Facilitator: There you go. Well that might be a good note on which to finish.

Interviewee: Okay.

Facilitator: Thank you.

Interviewee: You're welcome.

Facilitator: Thank you so much.

Interviewee: Was that fine? I can talk til the cows come home.

Facilitator: Absolutely fantastic.

Interviewee: You were saying you wanted my - it was funny, because my husband used to cringe - after he got sick and wasn't working, he then Googled his wife. So that's the - standing with Julia, making a speech.

Facilitator: That's a great photo.

Interviewee: And it's on YouTube if you…

Facilitator: Okay, yeah.

Interviewee: Clean Start launch.

Facilitator: Great.

[Part 3]

Interviewee: Yeah, so that sort of - it's what Lyndal put in to - and that's what they [unclear].

Facilitator: And Lyndal would have that, wouldn't she?

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: Would she share that?

Interviewee: Or you can take…

Facilitator: Take a photo?

Interviewee: Yeah.

Facilitator: Okay.

Interviewee: It goes - yeah.

Facilitator: Can you tell us about your…

Interviewee: I didn't get to go. I knew she was up to something, but - yeah. It was after the fact.

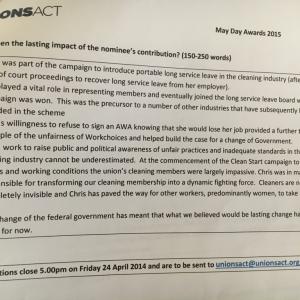

Facilitator: So it was an award for recognising contributions to women's advancement in unions that was awarded to you May Day 2015.

Interviewee: Yep. That was the nomination.

Facilitator: Lyndal had nominated you for that.

Interviewee: Yeah. That's what they read out on the night.

Facilitator: Okay, and it's got a great quote from you at the bottom here, if you can read that out.

Interviewee: Because we can't let the bastards win, yeah. Then there's more over the page. That was part of the campaigns that I've done.

Facilitator: Excellent. All right.

Interviewee: I'd forgotten that, yes, otherwise…

Facilitator: I will…

END OF TRANSCRIPT